Myanmar (Burma)

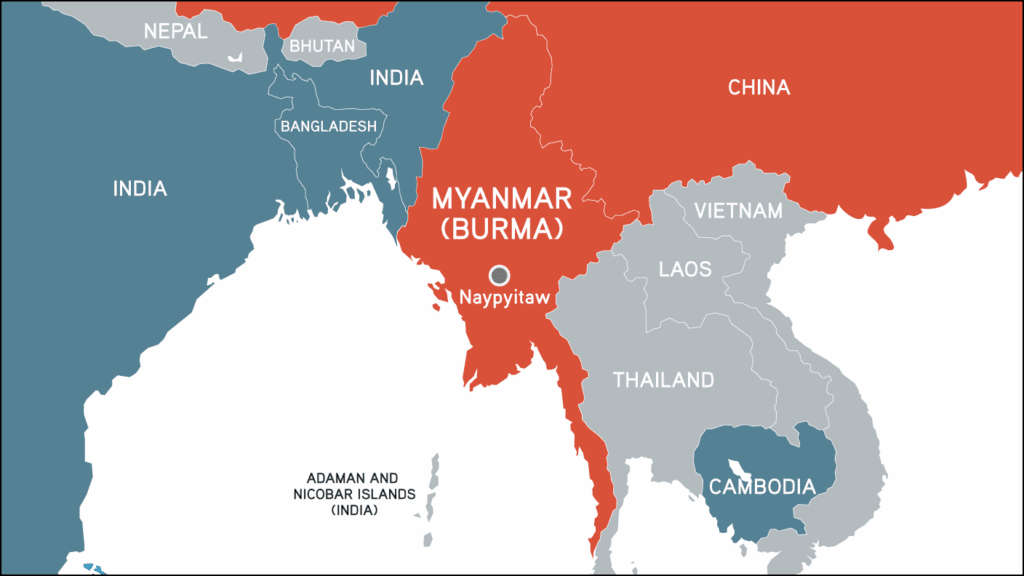

Populations in Myanmar are facing crimes against humanity and war crimes perpetrated by the military and armed groups following the February 2021 coup.

BACKGROUND:

Since the February 2021 military coup and prolonged states of emergency in Myanmar (Burma), the military – known as the Tatmadaw – has perpetrated widespread violations, compounding an existing human rights and humanitarian crisis in the country. Peaceful mass protests against the coup were met with brutal crackdowns. Civilian militias, known as People’s Defence Forces (PDFs), formed as part of an armed resistance. The junta has retaliated with relentless airstrikes, scorched earth campaigns and other systematic attacks on civilian areas, while denying or blocking humanitarian aid to civilians, particularly in the anti-military strongholds of Magway and Sagaing regions and Chin, Kachin, Shan, Kayah and Karen states.

Attacks by the junta and clashes with other armed groups threaten civilians, with 13 of Myanmar’s 15 states and regions affected by conflict. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has documented abuses against aid workers and the burning alive, dismembering, raping and beheading of civilians unable to flee attacks. At least 7,461 people have been killed in attacks by the junta, 3.6 million have been displaced and 21.9 million need assistance – an increase of one million from 2024. Last year also saw the highest civilian casualties since the coup, according to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. Anti-junta armed groups also threaten civilians and have been accused of torture, extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, forced recruitment and other abuses.

On 27 October 2023 a coalition of ethnic resistance organizations (EROs) launched “Operation 1027,” capturing military outposts across the country. Other groups, including some PDFs, and the Arakan Army (AA), an ERO in Rakhine State, subsequently increased attacks. In response to growing armed resistance the junta has responded with intensified – often indiscriminate, disproportionate or targeted – attacks on civilians.

The junta has also intentionally stoked inter-communal conflict between the ethnic Rakhine and Rohingya communities. Following significant advances in December 2024, the AA now controls all of Rakhine State, except for the capital and two smaller areas. Throughout the AA’s takeover, the UN reported violence against Rohingya civilians and displacement. Prior to the coup, in August 2017 the military launched so-called “clearance operations” in Rakhine State with the purported aim of confronting the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army. During those operations, the majority of Myanmar’s Rohingya population were forced to flee, leaving over 900,000 Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Despite increasing risks, the junta and Bangladesh have promoted a “pilot repatriation program” for Rohingya to return to Myanmar.

In April 2021 the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) adopted a “Five-Point Consensus (5PC),” which called for a cessation of hostilities, among other steps. No progress has been made in its implementation. In December 2022 the UN Security Council (UNSC) passed the first and only resolution on the country, demanding an end to the violence. The UN Human Rights Council (HRC) has adopted several resolutions on the crisis, including one urging member states to halt the sale of aviation fuel to the junta. Many governments have imposed targeted sanctions on Myanmar’s leaders, military-affiliated companies and others who enable their crimes, suspending development funds, imposing arms embargoes, banning dual-use goods and halting the supply of aviation fuel.

In 2018 the HRC-mandated Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar concluded that senior military officials, including General Min Aung Hlaing, should be prosecuted for genocide against the Rohingya and for crimes against humanity and war crimes in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan states. Several processes are underway to investigate and hold perpetrators accountable for crimes against the Rohingya, including the UN Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar (IIMM) and a trial at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) initiated by The Gambia accusing Myanmar of violating the Genocide Convention. On 27 November 2024 the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) applied for an arrest warrant for General Min Aung Hlaing for the crimes against humanity of deportation and persecution of the Rohingya. Courts in the Philippines and Türkiye have filed cases under universal jurisdiction. On 13 February 2025 an Argentine court also issued arrest warrants for 25 officials, including General Hlaing, former State Counsellor of the civilian government overthrown by the junta in 2021, Aung San Suu Kyi, and former President Htin Kyaw for genocide and crimes against humanity perpetrated against the Rohingya.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS:

In a 2 September report, OHCHR warned of an increasingly dire situation in Rakhine State, where clashes between the military and the AA have trapped Rohingya and ethnic Rakhine civilians in cycles of violence. The report details widespread abuses, including indiscriminate attacks, destruction of villages, forced recruitment, denial of humanitarian aid and mass displacement. Since November 2023 approximately 150,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh, further compounding the conditions facing nearly one million refugees in overcrowded camps.

The report also highlights new military tactics, including fertilizer-based explosives and armed paramotors used to drop munitions with little precision or warning. On 6 October a paramotor attack on civilians at a religious festival in Chaung-U township, Sagaing Region, killed at least 24 people. According to OHCHR, Sagaing remains one of the most targeted areas, with at least 108 airstrikes between 28 March and 31 May 2025 that killed 89 people.

Meanwhile, torture in detention centers – including electric shocks, strangulation and sexual violence against detainees, including children – remains pervasive. The junta has arbitrarily detained civilians perceived as opposing its rule with more than 22,569 people currently in detention.

On 30 September a High-Level Conference on the Situation of Rohingya Muslims and Other Minorities in Myanmar was hosted at the UN General Assembly to renew attention to the crisis and press for solutions.

On 26 November the IIMM warned that abuses amounting to mass atrocities are likely in the lead-up to elections scheduled for 28 December, noting that the polls will not be free or fair and violate the country’s constitution.

ANALYSIS:

Impunity for past atrocities has allowed the military to continue widespread and systematic abuses, especially against ethnic minorities and those seen as opposing the junta. Operation 1027 poses the most serious challenge to the junta since the coup. The military’s pattern of sexual and gender-based violence continues against those perceived as opposing the junta. The Rohingya face heightened risk of genocide and other atrocities due to junta-stoked inter-communal tensions and attacks by armed groups, including the AA.

Populations face a heightened risk of targeted attacks and increasingly repressive measures as the junta seeks to retake territory, suppress resistance and secure international legitimacy ahead of the elections.

Divisions within ASEAN and the UNSC, and ASEAN’s strict commitment to the 5PC, coupled with increasing influence and support by China to the junta, have hampered the development of a coordinated international response to atrocities in Myanmar. Despite extensive targeted sanctions, fuel and arms continue to be shipped into Myanmar, including from entities based in countries imposing sanctions.

The coup, ongoing hostilities and a lack of trust complicate the prospects for the safe, dignified and voluntary repatriation of Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh.

RISK ASSESSMENT:

-

-

- Impunity for decades of atrocities perpetrated by the military.

- History of institutionalized persecution and discrimination against ethnic minority groups.

- The military’s continued access to weapons, aviation fuel and money, providing the means to perpetrate atrocities.

- Indiscriminate attacks on civilian infrastructure.

- Increasing desperation of the junta to quell armed resistance, especially ahead of the elections.

-

NECESSARY ACTION:

The UNSC should impose a comprehensive arms embargo and targeted sanctions on Myanmar, ensure continued reporting on the crisis and refer the situation to the ICC. All UN member states, regional organizations and the UNSC should impose sanctions on Myanmar’s oil, gas and banking sectors and block the military’s access to arms and fuel. Foreign companies should immediately divest and sever ties with all military-linked businesses.

The international community should refrain from recognizing the junta as Myanmar’s legitimate representative, including after the elections, and should publicly denounce the polls. ASEAN member states should condemn the Tatmadaw, deepen engagement with the exiled National Unity Government and urgently reassess the 5PC.

More states should formally intervene in the ICJ case. All those responsible for atrocity crimes, including senior military leaders, should face international justice.

EROs must operate within the parameters of international humanitarian and human rights law.

For more on the Global Centre’s advocacy work on the situation in Myanmar, see our Myanmar country advocacy page.

Atrocity Alert No. 463: Democratic Republic of the Congo, Venezuela and Myanmar (Burma)

Related Content

The Concluding Stage of The Gambia v Myanmar Genocide Case Before the International Court of Justice

Expert Voices on Atrocity Prevention Episode 52: Tom Andrews