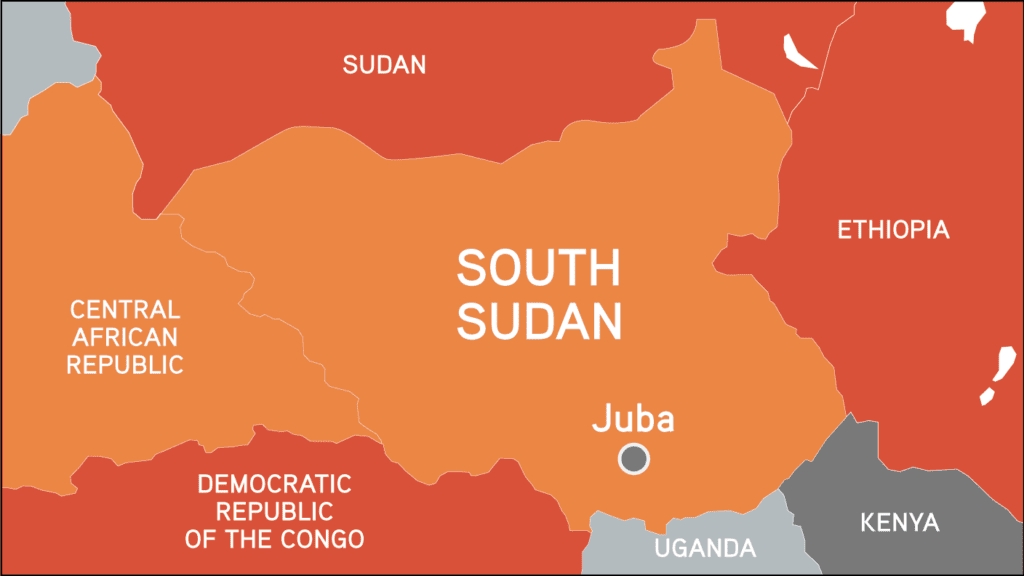

South Sudan

Ongoing localized and inter-communal violence, as well as political infighting, pose a pervasive threat to civilians in South Sudan.

BACKGROUND:

Since gaining independence in 2011, South Sudan has experienced persistent conflict and atrocities, with successive phases of violence threatening civilians across the country. The civil war between December 2013 and August 2015 resulted in an estimated 400,000 deaths, with both the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) and the SPLA-In Opposition perpetrating widespread atrocities, including extrajudicial killings, torture, child abductions and sexual violence. While multiple agreements were signed between 2015 and 2018, including the 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS), their partial implementation has allowed instability and localized conflict to persist, including intermittent fighting and ethnic violence.

The R-ARCSS aimed to end the civil war and establish a path toward stability, but delays in its implementation have also prolonged political tensions. The transitional period has been extended multiple times, with President Salva Kiir announcing another two-year extension on 13 September 2024, postponing the country’s first elections to December 2026 due to the lack of necessary reforms and infrastructure. The Transitional Government of National Unity (TGoNU) has struggled to implement essential provisions of the R-ARCSS, such as security sector reforms, armed forces unification, constitutional drafting, and governance reforms. The country’s national army, the South Sudan People’s Defense Forces (SSPDF), remains largely aligned with different factions and lacks unified command or professional training. The persistent failure to fulfill these key provisions, including security arrangements and electoral preparations, has raised concerns among states and the UN about the viability of South Sudan’s transition.

Grave human rights violations and abuses continue as populations face frequent inter-communal violence and sub-national clashes. Senior political and military leaders have also manipulated long-standing enmities between rival ethnic communities, enabling national level political dynamics to spark local conflicts. Tensions between the two main political parties, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement and the SPLM-In Opposition (SPLM-IO), over access to resources and political appointments have led to violent clashes and serious human rights violations, including widespread sexual violence, particularly against women and girls. Between July and September 2024, the Human Rights Division of the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) documented 206 incidents that resulted in at least 299 civilians killed, 310 injured, 151 abducted and 32 subjected to conflict-related sexual violence.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, over 9 million people – more than two thirds of the population – need humanitarian assistance. An estimated 1.8 million people remain internally displaced and 2.29 million have fled to neighboring countries.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS:

In January 2025 UNMISS reported that communal violence remains the primary driver of conflict and continues to exact a heavy toll on civilians. A UN inter-agency assessment revealed that more than 26,000 people were displaced during December due to violence in areas from Tambura to nearby Ezo and Nagero counties in Western Equatoria State. South Sudan’s Relief and Rehabilitation Commission reported that same month that over 15,000 people were displaced and properties destroyed in Gumuruk, part of the Greater Pibor Administrative Area.

On 31 January violent clashes erupted between pastoralists and settled communities in Magwi County in Eastern Equatoria State, spreading to Agoro, Chomboro, Obama and Ayiii villages. The escalating violence between these communities has fueled fear and forced many civilians to flee from affected areas in Eastern Equatoria and Lokiliri in Central Equatoria.

Since mid-February Upper Nile State has experienced heightened instability amid clashes between the SSPDF and the “White Army,” a loosely organized militia composed mainly of youth from the Nuer ethnic community and suspected to be loyal to Vice President and SPLM-IO leader Riek Machar. An attack on a market in Nasir on 14 February triggered violent confrontations, with local youth using heavy weaponry, resulting in at least 21 deaths and the displacement of thousands. On 7 March a UN helicopter evacuating South Sudanese soldiers from Nasir was attacked, resulting in the deaths of a South Sudanese general, approximately 27 soldiers and a UN crew member. Following this incident, the government arrested several officials allied with Machar and South Sudanese troops were deployed around Machar’s residence. In response to rising tensions, Uganda reportedly deployed special forces to Juba to protect President Kiir.

ANALYSIS:

The prolonged delays and ongoing friction within the TGoNU fuel local conflicts, as political and military leaders continue to exploit long-standing ethnic divisions. The repeated failure to uphold multiple peace agreements, continued political competition and mobilization of armed groups show a lack of genuine commitment to a political solution by South Sudan’s leaders. Their focus on preserving personal power allowed mistrust to reinvigorate ethnic tensions and fuel violence across the country. Delays in reforming the security sector appear to be a deliberate strategy by President Kiir to retain dominance. The recent violence in Upper Nile State and arrests have heightened political tensions in Juba, further straining the fragile relationship between Kiir and Machar and raising concerns about the stability of the peace process.

The disappearance of civic and political space diminishes opportunities for civilians to participate in constitution-making, transitional justice, national elections and other essential democratic processes and may give rise to grievances that become a trigger for atrocity crimes. While holding elections under the current circumstances risked triggering atrocities, frequent delays in the democratic process can foment increased instability and frustration among the public. This can erode trust in the government’s commitment or capacity to organize free and fair elections and lead to unrest or violence.

The influx of small arms, light weapons and ammunition during South Sudan’s civil war has increased the enduring risk of atrocities, with the accessibility of weapons to civilians and youth groups making inter-communal clashes more deadly. The armed conflict and continued violations of ceasefire agreements underline the importance of the UN Security Council (UNSC)-imposed arms embargo and targeted sanctions.

A pervasive culture of impunity continues to fuel resentment, recurring cycles of violence and atrocity crimes. Neither the government nor opposition groups have held perpetrators within their own ranks accountable for past or current atrocities. Despite the signing into law of the Commission for Truth, Reconciliation, and Healing Act 2024 and the Compensation and Reparations Authority Act 2024 in November, none of the transitional justice mechanisms provided for by the R-ARCSS, including the Hybrid Court, have been established or are operational.

RISK ASSESSMENT:

-

- A security crisis caused by, among other factors, delays in implementing the R-ARCSS, absence of a unified army under national command, weak state institutions and lack of capacity to prevent atrocities and address rising political and inter-communal tensions.

- Impunity for serious violations of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and International Human Rights Law (IHRL), atrocity crimes or their incitement.

- Past and present serious inter-communal tensions and conflicts, the mobilization of armed groups along ethnic lines and the politicization of past grievances.

- Capacity to commit atrocity crimes, including availability of personnel, arms and ammunition.

- Repression of civic and political space.

NECESSARY ACTION:

With nearly two years to prepare, the transitional government, with support from the international community, must take decisive action to establish the essential conditions for conducting genuine and peaceful elections. The TGoNU should also respect civic and political space and take all necessary measures to guarantee the participation of civilians in essential democratic processes.

All armed groups must immediately cease hostilities and respect IHRL and IHL to prevent further civilian harm. The TGoNU must make every effort to stop the fighting, address the root causes of inter-communal violence and ensure the safety and security of all populations.

The international community should exert increased diplomatic pressure on all parties to the R-ARCSS to ensure its full implementation. The TGoNU must urgently reform the security sector, in line with the R-ARCSS, and promote accountability and professionalism within all security forces. The UNSC must impose further targeted sanctions against any individuals who undermine the peace process. The African Union (AU), Intergovernmental Authority on Development and neighboring countries should actively enforce the existing arms embargo.

The AU and TGoNU must expeditiously establish the Hybrid Court and prosecute individuals responsible for past atrocities, regardless of their affiliation or position.

Atrocity Alert No. 441: South Sudan, Ukraine and Democratic Republic of the Congo

Related Content

Atrocity Alert No. 444: Nigeria, Haiti and South Sudan

Resolution 2781 (South Sudan) S/RES/2781