Unwilling and Unable: The Failed Response to the Atrocities in Darfur

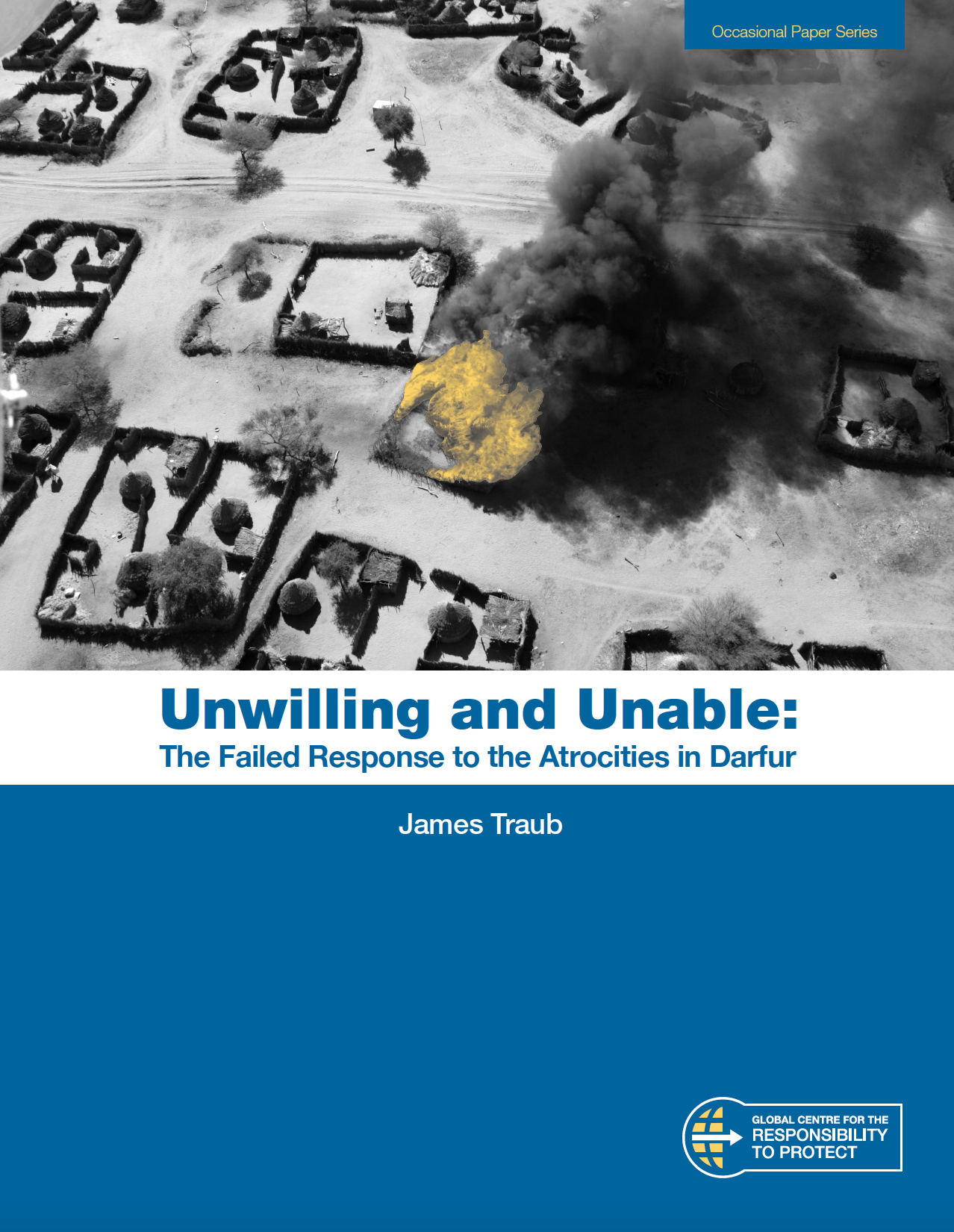

Starting in mid-2003, the government of Sudan responded to an armed rebellion in the western state of Darfur with a massive campaign of killing and expulsion carried out both by regular army troops and by a proxy force known as the Janjaweed. United Nations (UN) sources estimate that this orchestrated effort led to the death of at least 300,000 people, while over two million were forcibly displaced. Extensive documentation by the UN, human-rights organizations and the media leaves no doubt that the Sudanese government and the Janjaweed committed war crimes and crimes against humanity, and did so over a period of many years. Yet all attempts to stop the killing, whether by neighbors, regional organizations, Western states or the UN Security Council, proved ineffective. In 2005, states—including Sudan—unanimously agreed that they had a responsibility to protect populations from mass atrocities; but this abstract commitment has had little effect on the Sudanese government or on other UN member states who had made this pledge.

This report from the Global Centre for The Responsibility to Protect examines the entire sequence of events and asks, first, why the world manifestly failed to stem the violence, and, secondly, what ought to have been done in the face of a state apparently determined to perpetrate atrocities upon its own people. Specifically, the study seeks to pinpoint when during the early period action might have either prevented or minimized the violence, and to stipulate what should and could have been done by many different actors who, at various times, engaged with the government of Sudan. Consistent with the doctrine of the responsibility to protect, the report focuses not on scenarios of military intervention, but rather on the vast array of instruments, consensual and coercive, available to the international community—diplomatic engagement and mediation, targeted sanctions, the introduction of peacekeeping forces and international criminal prosecution.

Across the many years of violence, these instruments were in fact deployed—but tardily and timidly. States could not agree on difficult measures, and Khartoum was quick to exploit the cracks in the international response. The report concludes with a series of lessons which can be taken from the conflict in Darfur and applied to other settings, especially those in which a state intentionally commits abuses against its own citizens. Among these are the imperative for the Security Council and other organs to heed the early or premonitory signs of violence and that over time, conflicts grow more intractable and complex, effectively precluding modes of action which might have worked at an earlier point. The report also highlights the inherent tensions or even contradictions of engagement, such as the sometimes rival claims of “peace” and “justice.” The goal of the responsibility to protect, the report concludes, is not “to mete out just desserts,” but to stop atrocities.

Download PDF Version:

Related Content

11th Meeting of the Global Network of R2P Focal Points Outcome Document