Remarks at UN General Assembly Side-Event on “Confronting Hate and Protecting Rights”

Statement delivered by Ms. Savita Pawnday, Deputy Executive Director, at a UN General Assembly Side-Event on “Confronting Hate and Protecting Rights: UN Initiatives to Promote Inclusion and Ensure Freedom of Expression and Freedom of Religion or Belief” hosted by the Global Centre together with the governments of the United Kingdom, Argentina and the Netherlands, as well as Article 19, Club de Madrid, Jacob Blaustein Institute, and the UN Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect.

Your Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen,

There exists a correlation between hate speech and the commission of atrocity crimes. And this correlation becomes more significant if hate speech and inflammatory rhetoric against certain populations is propagated by political leaders, religious leaders and people with celebrity who have political and social capital. The more hate speech is employed by political and religious leaders, the more it becomes part of the mainstream and creates a permissive and toxic environment where calls for violence against the “hated” group become normalized.

Generally hate speech marginalizes a particular group and depicts them as a “threat.” This can then mobilize the majority or other groups to take action to defend themselves from this perceived threat on their culture, economic well-being, religion, etc. It can encourage perpetrators to demonstrate their loyalty and willingness to “defend” their community by engaging in violence. And if there are any triggering events, such as an election, it can lead to the commission of atrocities.

Many of the world’s darkest chapters were preceded by discriminatory public discourse and demonization of certain groups and by the spreading of fear among the population to justify atrocities. They were defining features of the Holocaust, and the genocides at Srebrenica and in Rwandan nearly 25 years ago. Radio broadcasts in Rwanda advocated for violence against the Tutsi, calling for populations to “exterminate the cockroaches.”

These characteristics were also visible in more recent atrocity situations, including the post-election violence in Kenya in 2007-2008, where hate speech used by politicians to achieve personal political gains mobilized their supporters to engage in targeted ethnic violence, resulting in the death of over 1,100 people and the displacement of over half a million.

In Myanmar discriminatory policies targeting the Rohingya population were in place for decades. This discrimination did more than just marginalize the Rohingya, it stigmatized the group as being outsiders or foreigners. The lack of accountability for those with influence – especially senior Buddhist religious leaders – who had expressed dangerous anti-Rohingya and anti-Muslim sentiments established over time an environment that was permissive of hate speech and violence targeting Rohingya villages. The growing acceptance of anti-Rohingya sentiments among the population emboldened the government to further restrict their rights and eventually undertake the so-called “clearance operations” in 2017 that have been determined to have been genocidal in their intent.

The political manipulation of inter-communal tensions has also facilitated the commission of atrocities in the Central African Republic, where incitement to violence against ethnic and religious groups has become a defining feature of the conflict. Amidst pre-existing mistrust between communities, inflammatory rhetoric was used to deepen the divide between Muslim and Christian communities. In response, armed groups perpetrated violence and atrocities – including war crimes and crimes against humanity – and justified their actions as necessary self-defense against perceived threats.

We have seen this dynamic play out again in countries where atrocities have been committed.

MODERATOR QUESTION: FROM A CIVIL SOCIETY PERSPECTIVE, WHY DO YOU CONSIDER THE NEW UN STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN ON HATE SPEECH TIMELY AND IMPORTANT?

When UN Secretary-General Guterres launched the Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech, he noted that in the world today we can see a “groundswell of xenophobia, racism and intolerance, violent misogyny, and also anti-Semitism and anti-Muslim hatred.”

Across the world we are seeing the resurgence of right-wing populist political leaders who preach nationalism, simple majoritarianism, and a narrow and twisted idea of what it means to be patriotic.

No society is immune. It is not a problem that only happens in Myanmar or Central African Republic or South Sudan. In Europe the refugee crisis has triggered increased racism and xenophobia. Hate Speech against migrants have led to numerous attacks against refugees and asylum seekers in Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, France, Finland, and the Netherlands.

If radio was the tool in Rwanda– Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp have become the method of today. Also, it is not just some guy sitting in his basement or belonging to an extremist group who is spreading this hatred. With WhatsApp, your favorite uncle or your cousins are potentially sharing a false or exaggerated message of how Muslims or migrants are raping and pillaging your country or region or are a threat to your cultural and religious values.

Just two weeks ago we were monitoring reports of WhatsApp messages spread through South Africa, advocating for people to “kill everyone person from outside this country.” While the situation has not risen to the level of mass atrocities, we can see how the normalization of this rhetoric could result in widespread xenophobic attacks.

The new Action Plan launched by the Secretary-General is emphasizing the importance of addressing and countering hate speech in the world today and creates a new momentum, but it is not a panacea. For a civil society organization like mine it will provide the institutional space to engage the UN and other member states in systematically addressing hate speech. The UN needs to put in place capacities that can monitor hate speech. This includes monitoring through UN Peacekeeping missions in South Sudan, Central African Republic and elsewhere where a spike in inflammatory rhetoric can elevate existing tensions and possibly lead to the commission of atrocities, as well as through UN presences in other countries at high risk, such as Myanmar.

States and local actors need to strengthen legislative and institutional frameworks to guarantee principles of non-discrimination, ensure the presence of various communities in political and public offices, and investigate all cases of discriminatory behavior or dangerous public discourse. In some cases, states should also strengthen and empower election commissions to take robust action against those who use inflammatory rhetoric that incites violence during campaigns.

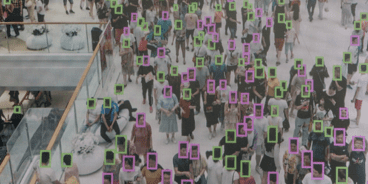

Social media companies often lack the expertise and resources to structurally monitor and address inappropriate content and hate speech. They currently rely on a combination of artificial intelligence, user reporting, and “content moderators” to determine whether content is appropriate or not. Often external contractors are tasked with monitoring harmful content in a particular country or region despite not even speaking the local language or understanding the political, historical or social context. We would like to see all social media companies establishing more systematic procedures to monitor their platforms and also appoint human rights and atrocity prevention Focal Points who can then be mobilized by international and national entities.

Related Publications

Atrocity Alert No. 423: Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Ukraine and Atrocity Risks and Content Moderation