Recommendations for the 50th Session of the Universal Periodic Review

Your Excellency,

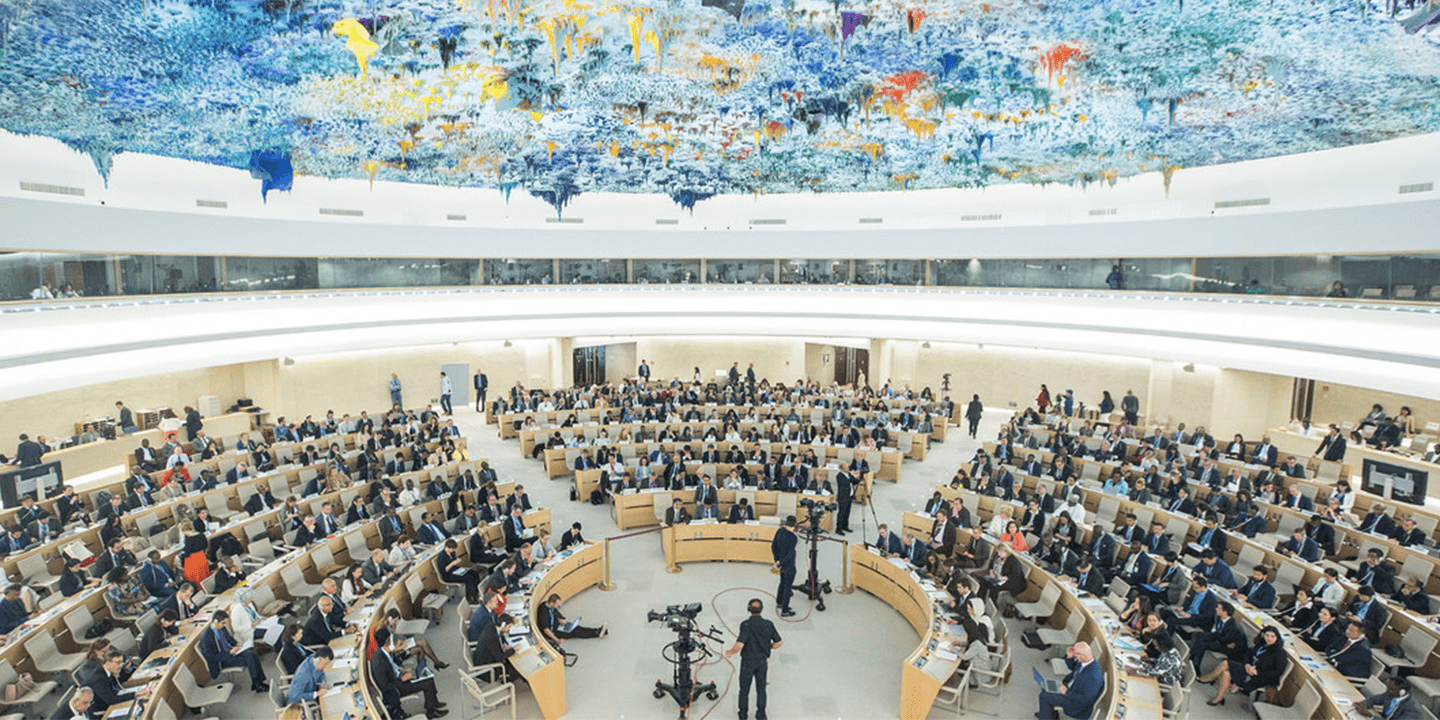

The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect is writing to you regarding the 50th session of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) in Geneva.

In 2005 heads of state and government unanimously agreed on the responsibility of states to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. Under the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), it is the primary responsibility of each individual state to protect their own population and the responsibility of the international community to assist them in doing so. The UPR can play an important role in assessing each country’s institutional preparedness to protect human rights and prevent mass atrocities. During the 50th session of the UPR working group, the Global Centre would therefore like to respectfully encourage you to provide all states that are under review with the following recommendations, where applicable:

-

-

- Expeditiously appoint an R2P Focal Point – a senior government official responsible for the promotion of mass atrocity prevention at the national, regional and international level;

- Sign, ratify and implement the core instruments of International Human Rights Law (IHRL) and International Humanitarian Law (IHL), including the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Additional Protocols I and II to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, Arms Trade Treaty and 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict;

- In keeping with R2P’s Pillar II, request support from other states, as well as regional and international organizations, when atrocity risks exist that cannot be addressed by your state alone;

- Ensure that all national security forces respect human rights and IHL and fulfill their responsibility to protect all populations within the territory of your state, regardless of race, gender, nationality, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation or any other status;

- Support accountability for atrocity crimes and all relevant institutions of international justice;

- Issue open invitations to HRC-mandated Special Procedures and fully cooperate with all other HRC mechanisms and procedures;

- Protect human rights defenders and the media, as well as the rights of civil society to operate freely, safely and independently;

- Consult and utilize the Framework for Action for the Responsibility to Protect, written by the Global Centre and the Asia-Pacific Centre for R2P, to assess gaps and identify opportunities to address national atrocity risks.

-

In addition to these general recommendations, we respectfully ask you to consider the tailored recommendations provided below for Belarus and Libya.

Belarus

In the five years since Belarus’ last UPR cycle in November 2020 the human rights situation has significantly deteriorated. Despite formally supporting recommendations on the protection of peaceful assembly, freedom of expression and the need for accountability for and prevention of torture and ill-treatment, populations in Belarus continue to face systematic patterns of repression and a complete crackdown on fundamental rights. The Group of Independent Experts (GIE) on the Situation of Human Rights in Belarus has documented the widespread use of arbitrary detention – often accompanied by torture or ill-treatment – and politically motivated persecution to silence dissent. The GIE concluded that Belarusian authorities have committed the crimes against humanity of imprisonment and persecution on political grounds. Despite waves of presidential pardons throughout 2025, the overall number of people unjustly imprisoned remains high.

Furthermore, Belarusian authorities have reshaped the country’s legal system to eradicate all dissent under the guise of legality. Courts, law enforcement and security services operate together to suppress opposition. Following the 2020 crackdown, the government adopted a set of legislative reforms introducing new criminal and administrative offences, extending the death penalty, restricting freedom of assembly and association and curtailing freedom of expression through expanded surveillance. The UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Belarus has documented the routine misuse of so-called counterterrorism and anti-extremism laws against opposition politicians, human rights defenders, journalists and activists. Recent legal changes have also enabled discriminatory and repressive measures against LGBTQIA+ individuals.

The authorities have intensified transnational repression and collective punishment. Belarusians forced into exile since 2020 face politically motivated charges and in absentia trials lacking due process, while reprisals are increasingly targeting family members of individuals deemed disloyal by the authorities.

The government has increasingly rejected findings from human rights bodies, obstructed independent monitoring and refused to cooperate with international mechanisms. Belarusian authorities consistently fail to investigate credible reports of violations and abuses, perpetuating a climate of fear and impunity. No meaningful domestic avenues for accountability exist.

The Global Centre therefore urges to include the following recommendations to Belarus during the UPR session on 3 November:

-

-

- Release immediately and unconditionally human rights defenders, lawyers, trade union members, opposition politicians, journalists and others convicted in retaliation for exercising their civil and political rights and guarantee that they can carry out their work without fear of reprisal.

- Stop the practice of politically motivated prosecutions and other acts of repression against Belarusians in exile and their family members.

- Ensure the absolute prohibition of torture and ill-treatment, immediately cease the practice of incommunicado and coercive psychiatric detention and bring detention conditions in line with international standards.

- Provide independent monitors with unimpeded and confidential access to all places of detention, including a standing invitation to the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.

- Promptly initiate independent, impartial, effective and transparent investigations into all past human rights violations, particularly those that the GIE has determined there are reasonable grounds to believe amount to crimes against humanity, and ensure that all victims obtain redress and remedy.

- Ratify the Rome Statute and implement the statute in national legislation, including by incorporating provisions to cooperate promptly and fully with the ICC.

- Re-engage in a meaningful and non-selective manner with UN human rights bodies and mechanisms. With the help of these bodies and the participation of all relevant stakeholders, including Belarussian civil society organizations outside the country, develop a comprehensive plan of legislative and institutional reforms addressing the structural causes of the human rights violations documented since May 2020.

-

The Global Centre further respectfully encourages you to consider the following advanced question for the review of Belarus:

-

-

- Given the lack of implementation of supported recommendations from the previous UPR cycle, what steps does the government plan to take to investigate, ensure accountability for and prevent crimes against humanity – specifically imprisonment and persecution on political grounds – documented by the GIE?

-

Libya

Libya continues to face credible allegations of serious human rights violations that may amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity. These abuses are deeply rooted in over a decade of armed conflict, militia rule and institutional collapse.

Despite ongoing political dialogue, Libya’s transition to a unified government remains stalled. Elections have been repeatedly delayed and progress continues to be disrupted by intermittent violence between rival militias. On 12 May 2025 clashes erupted in Tripoli following the killing of Abdelghani al-Kikli, the influential leader of the Stability Support Apparatus (SSA) armed group. His death triggered violent confrontations between SSA forces and factions aligned with the Government of National Unity (GNU), led by Prime Minister Abdulhamid al-Dbeibah. In a speech on 17 May, al-Dbeibah publicly justified the killing, accusing al-Kikli of orchestrating violence and undermining the state.

Following the renewed violence, Prime Minister al-Dbeibah portrayed the events as a security success and launched a campaign to “eliminate irregular groups.” Armed factions in Tripoli subsequently used live ammunition to disperse protesters criticizing the GNU. These actions raise concerns about the GNU’s tolerance for dissent and its reliance on armed groups to exert control.

The SSA is one of several powerful, quasi-state armed groups operating with impunity in Libya and has long been implicated in enforced disappearances, torture and other serious abuses – many of which may constitute crimes against humanity. Migrants, refugees and asylum seekers detained in SSA-controlled facilities have suffered rape, torture, sexual violence, forced labor and extortion.

Authorities also continue to uncover mass graves across the country, many containing the remains of migrants with gunshot wounds, raising serious concerns over extrajudicial killings by armed groups. In June 2025 multiple mass graves were discovered near detention centers in Kufra and Tripoli, both reportedly linked to the SSA. These discoveries reflect a broader, long-standing pattern of violence against migrants and refugees in Libya.

The country lacks a domestic asylum system and criminalizes irregular entry, leaving tens of thousands – many fleeing war or persecution – vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Migrants are routinely detained in formal and informal facilities controlled by militias, traffickers or state-affiliated forces, where they endure inhumane conditions, including torture, starvation, forced labor and sexual violence. Women, particularly those from Sub-Saharan Africa and Sudan, face heightened risks of rape and sexual exploitation. Many are traded between armed groups or coerced into sex in exchange for food and safety. Collective expulsions across Libya’s desert borders, often without due process or access to protection, have also led to numerous deaths.

In June 2020 the HRC established the Independent Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) on Libya, which concluded its mandate in 2023. The FFM found that armed groups, state authorities and security forces were responsible for widespread violations and abuses — including murder, torture, rape, enslavement and enforced disappearances — many of which it determined amount to crimes against humanity. The FFM urged the implementation of accountability mechanisms, including international prosecutions.

The ICC has had jurisdiction over Libya since 2011 under UN Security Council Resolution 1970. The Court has issued several outstanding arrest warrants and sealed warrants for individuals implicated in grave crimes, including abuses against migrants and asylum seekers.

The Global Centre therefore urges you to include the following recommendations during the review of Libya during the UPR session on 11 November:

-

-

- Strictly adhere to all obligations under IHL, including the principle of distinction, the protection of civilians not directly participating in hostilities, and the protection of civilian objects, including infrastructure and health facilities.

- Facilitate immediate and transparent investigations and accountability processes into human rights violations and possible war crimes and hold accountable all those responsible for such attacks, regardless of position or affiliation.

- Actively cooperate with the ICC, including assistance in executing outstanding warrants.

- Commit to ending Libya’s governing impasse and ensure tangible progress toward free, transparent and legitimate elections.

- Strengthen and implement robust strategies and measures to ensure the protection of and respect for the human rights of migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, victims of trafficking and members of other vulnerable groups in the context of irregular migration, especially women and children, by adhering to international standards, including respecting the principle of non-refoulement.

- Investigate and prosecute all human rights violations and abuses impacting migrants and asylum seekers, including kidnappings, torture, sexual violence, the sale of people as slaves and arbitrary detention.

-

The Global Centre further respectfully encourages you to consider the following advanced question for the review of Libya:

-

-

- Will the GNU commit to placing the protection and promotion of human rights at the center of its governance, including by ensuring that all affiliated armed groups and militias are held accountable for upholding IHRL and IHL?

-

Related Content