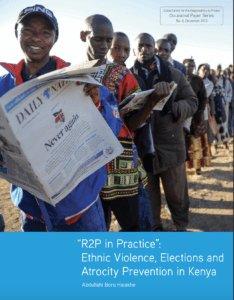

“R2P in Practice”: Ethnic Violence, Elections and Atrocity Prevention in Kenya

On the last Monday of 2007 dozens of ethnic Kikuyu families crowded into the Assemblies of God church in the village of Kiambaa seeking sanctuary from the violence engulfing their country. A disputed election and simmering resentment over decades of ethnic favoritism by the political elite had transformed Kenya from a perceived paragon of stability in East Africa into a killing zone. Just days after allegedly fraudulent election results had been released in late December more than 250 people were already dead, many killed by mobs armed with machetes and knives. The 400 people crowding into the Kiambaa church were terrified they might be next.

On Tuesday, in broad daylight, a crowd of ethnic Kalenjins, Luhyas and Luos surrounded the church, blocked the exits and set the building on fire. Most of the Kikuyu families inside were able to fight their way out and flee. However, at least thirty-five people were killed including a number of women and children who were burned alive. As the international media came to document the horror at Kiambaa, an elderly professor spoke for many Kenyans when he said that the scene at the church, “reminds me of Rwanda.”

Unlike Rwanda in 1994, Kenya did not descend into genocide, but the ethnic violence lasted weeks and claimed 1,133 lives. Hundreds of thousands of Kenyans were displaced or injured. The fact that the bloodletting was eventually halted was due in no small part to the efforts of international mediators, including former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan. Weeks of negotiations led to a power-sharing government and the promise of deep reforms to the entire political structure of Kenyan society. When the resulting agreement was publicly presented in February 2008, it was hailed by some commentators as the first example of “R2P in practice.”

This occasional paper by the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect examines the causes of widespread ethnic violence in Kenya during 2007-2008 and explores why the country was able to avoid similar violence during the March 2013 election. In particular the author, Abdullahi Boru Halakhe, focuses on the range of reforms implemented, often with international assistance, by the Kenyan government between 2008 and 2013. The report assesses the effectiveness of these preventive measures in protecting ordinary Kenyans from a recurrence of the sort of mass atrocity crimes, like the church burning at Kiambaa, which so shocked Kenyans and the world.

The report argues, however, that Kenya’s reform process is inchoate. In particular, there has been no accountability for those suspected of being most responsible for orchestrating mass atrocity crimes following the 2007 election. While a highly contentious process of trying the current President, Uhuru Kenyatta, and Vice President, William Ruto, at the International Criminal Court is underway, justice continues to be denied to the victims of the post-election violence. This paper seeks to explain how and why particular preventive efforts succeeded in Kenya in 2013 and what that means for the future of the Responsibility to Protect.

Download PDF Version

Related Content

Atrocity Alert No. 423: Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Ukraine and Atrocity Risks and Content Moderation