A legitimate, humane mission in Iraq to halt Islamic State extremism

Article by Hon. Gareth Evans in The Australian on how the principle of Responsibility to Protect should be applied to the situation in Iraq and what it would mean to do so.

The current Western military intervention in Iraq is not 2003 revisited, and Australia is right to be part of it. The action is being taken at the request of the Iraqi government, to support its own and Kurdish Peshmerga forces, so no question arises of any breach of international law even in the absence of express UN Security Council authorisation. Its objective is explicitly humanitarian, to protect civilian populations immediately at risk of genocide or other mass atrocity crimes from the marauding Islamic State militant forces, who in their march across Iraq have already perpetrated atrocities unrivalled in their savagery. And there is a reasonable prospect that it will be successful in meeting at least this immediate aim.

The intervention is not based, as was the attack on Saddam Hussein, on generalised human rights concerns, or beliefs — later proved completely unfounded — about that regime’s possession of weapons of mass destruction or support for terrorist organisations. It touches all the necessary bases of legality, legitimacy and likely effectiveness. In short, it is completely consistent, in a way the earlier action was clearly not, with the principles of the international responsibility to protect (R2P) people at risk of mass atrocity crimes that was embraced unanimously by the UN General Assembly in 2005.

Using military force for any purpose is never a decision to be taken lightly. Even if there are no legal issues, there are always risks involved, and always moral and prudential criteria that must be satisfied. Although such benchmarks have not yet been formally adopted by the UN or anyone else, there has been much international discussion during the past decade, mainly in the context of the R2P debate, as to what these should be, and a large measure of informal agreement is evident.

These generally accepted criteria of legitimacy are that the atrocities occurring or feared are sufficiently serious to justify, prima facie, a military response; that the response has a primarily humanitarian motive; that no lesser response is likely to be effective in halting or averting the harm; that the proposed response is proportional to the threat; and that the intervention will actually be effective, doing more good than harm.

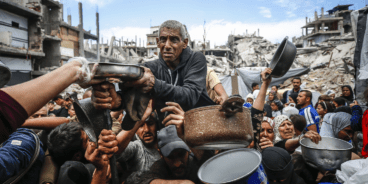

All these bases seem to be covered here. The available evidence is that the many thousands of men, women and children in northern Iraq — Shi’ites, Kurds or those perceived as Sunni apostates — remain at risk of genocidal slaughter by the advancing Islamic State forces.

The immediate US motive in mobilising air power is unquestionably to protect them, although obvious secondary objectives are to try to avoid further political disintegration of the region, and to cut off at source the risk of a new generation of jihadist terrorists ultimately terrorising the West.

The only question about proportionality that arises is whether the airborne attacks and supply drops will do too little, rather than too much, to address the immediate emergency. And this is not a case, as Syria has been until now, and Iraq in 2003 certainly was, where external military intervention can be argued to be likely to cause more harm than good. US air attacks and supply drops have already been crucial in allowing the Yazidis to escape entrapment in the Sinjar mountain range, relieving the siege of Amerli, and reducing the pressure on Iraqi Kurdistan, and hopefully will contain any further Islamic State advances of this kind.

Whether intervention on the present scale, which Australia is properly supporting, will reverse the gains made by the Islamic State in northern Iraq and succeed in re-establishing the constitutional integrity of the Iraqi state — let alone help change the dynamics of the conflict in Syria — is a completely different question. That will depend above all, as the Obama administration has made clear, on whether new Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi can reverse the disastrously divisive leadership of his predecessor, Nouri al-Maliki, and whether a genuinely inclusive government can quickly enable the so-far largely ineffectual Iraqi armed forces to get their act together.

Though some conservative American voices are baying for more to be done, it is very difficult to make a case for the US, Australia or anyone else sacrificing blood and treasure to try to prop up an Iraqi regime so demonstrably, at least until now, unable and unwilling to help itself hold the country together — and even harder to find anyone in Syria to support with reason and good conscience.

Widening war is bound to produce innocent civilian casualties; even 150,000 pairs of foreign boots on the ground were insufficient to stabilise Iraq after the horribly ill-judged 2003 intervention; and any Western military intervention with overtly political rather than simply humanitarian objectives runs the risk of inflaming sectarian Islamist sentiment. So as things now stand, the only justification — moral, political or military — for renewed external military intervention in Iraq is to meet the international responsibility to protect victims, or potential victims, of mass atrocity. To do any more would be to take us back into uncharted waters. But to do any less would be to abdicate our common humanity.

Both the Coalition government and the Labor opposition are to be praised for seeing the issue in these terms, as they manifestly do. It is not a matter of blindly embarking on yet another military adventure simply because we have been asked by our US allies to do so, but of being, and being seen to be, the good international citizens that we aspire to be.

It is possible to cast Australian support for this intervention in narrowly self-interested terms, in that we, along with many other nations, have a strong security interest in destroying new breeding grounds for jihadist terrorists who may directly threaten us.

But there is a larger national interest at issue here — one worth reputational gold — that of being, and being seen to be, a co-operative, engaged, principled player on issues of fundamental importance to the preservation of the global commons or our common humanity.

There can be no better demonstration of good international citizenship than a country’s willingness to act when it has the capability to help prevent or avert a mass atrocity crime.

Barack Obama has been criticised recently, in the context of his attitude to the Arab-Israeli peace process, as being “cerebral in a part of the world that’s looking for the visceral”. But his response, and now that of Tony Abbott and Bill Shorten, to the plight of those at risk of atrocity crimes in Iraq has been cerebral and visceral, and we and the world are the better for it.

Related Content

Atrocity Alert No. 437: Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Ukraine and Nigeria