Sudan

Populations in Sudan are enduring war crimes and crimes against humanity due to an armed confrontation between the Sudanese military, the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and allied militias. Non-Arab communities in Darfur are enduring crimes that may amount to acts of genocide perpetrated by the RSF.

BACKGROUND:

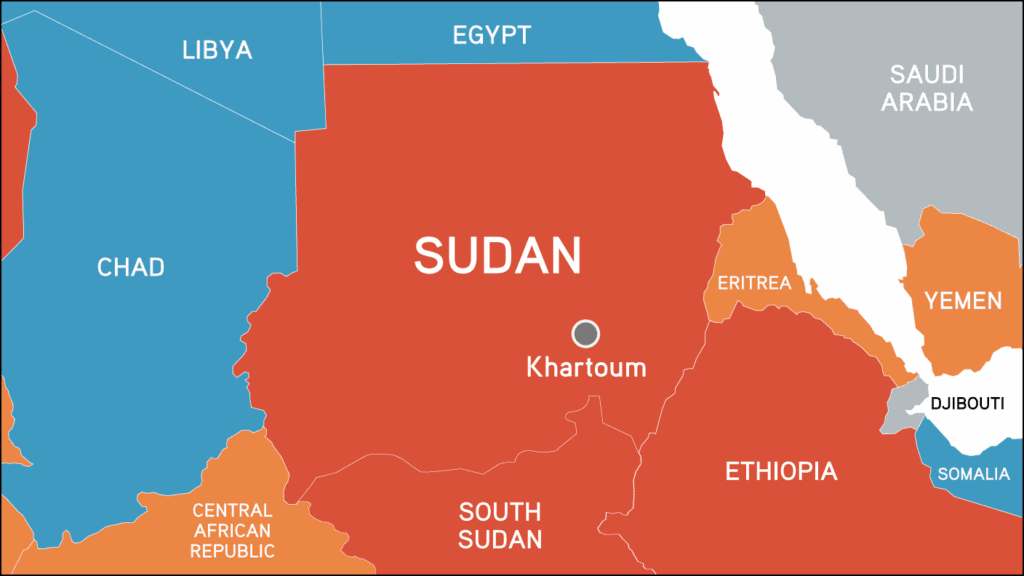

Since violent clashes broke out on 15 April 2023 between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), both parties have been fighting to preserve and expand their control in Sudan, while various allied militias have further complicated the conflict. The fighting has been characterized by indiscriminate and deliberate attacks against civilians and civilian objects, often with rocket shells, bombardments and heavy artillery, including in densely populated areas, as well as the widespread use of sexual violence, including rape, sexual assault, exploitation and sexual slavery. The UN Human Rights Council (HRC)-mandated Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) has concluded that the SAF and RSF and their allied militias are responsible for large-scale violations of human rights and International Humanitarian Law (IHL), many of which amount to war crimes and/or crimes against humanity. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that as of November 2025 13.9 million people are displaced, including 4.1 million who fled to neighboring countries.

The RSF have utilized the conflict to accelerate a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing and large-scale attacks targeting non-Arab communities in Darfur and other regions, perpetrating possible acts of genocide. Following the takeover of El Fasher in October 2025, the RSF now controls all of Darfur and is attempting to expand its control into the Kordofan region. Across both regions, fighting and attacks against civilians have intensified, causing mass displacement, with thousands fleeing their homes amid severe shortages of food, water and shelter.

The ongoing conflict has severely restricted access to lifesaving aid and essential services through targeted attacks, deliberate restrictions and looting of humanitarian supplies, triggering the world’s largest hunger crisis. An estimated 30.4 million people need assistance. As of October 2025, the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification Famine Review Committee confirmed famine conditions in El Fasher and Kadugli, South Kordofan. Reports indicate that dozens of people, mostly women and children, have died from malnutrition. Starvation has been used as a method of warfare, potentially amounting to the crime against humanity of extermination.

Sudan underwent multiple significant political changes after former President Omar al-Bashir was overthrown amid countrywide protests in 2019. Leadership was initially transferred to a joint civilian-military transitional Sovereign Council but the military – led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and supported by Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo – seized power on 25 October 2021. The current conflict erupted from mounting tensions between General Burhan, commander of the SAF, and General Hemedti, commander of the RSF, regarding the RSF’s integration into Sudan’s regular forces as part of a political agreement aiming to establish a new transitional civilian authority.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS:

On 26 October, after eighteen months of besieging El Fasher, the RSF captured the city following days of bombardment. Thousands have reportedly been killed, with reports and satellite imagery indicating a drastic escalation of targeted ethnic violence, extrajudicial killings and summary executions. Entire neighborhoods and medical facilities have been destroyed and humanitarian access, communication networks and escape routes are completely cut off. On 28 October more than 460 patients and their companions were reportedly shot and killed inside the Saudi Maternity Hospital, the only partially functioning medical facility in El Fasher. Satellite imagery suggests evidence of door-to-door executions, mass graves and the burning of objects that may be consistent with bodies. Nearly 100,000 people fled between 26 October and 14 November, while many others remain trapped in the city.

Prior to capturing El Fasher, the RSF significantly intensified attacks, including artillery shelling, drone strikes and ground incursions, killing at least 178 civilians at a mosque, a community kitchen and a displacement camp in and around Abu Shouk and the Daraja Ouala neigborhood. The RSF is also reportedly positioning long-range drones in South Darfur.

On 14 November the HRC held an Emergency Session on the human rights situation in and around El Fasher and requested that the FFM conduct an urgent inquiry into recent violations and abuses of International Human Rights Law (IHRL) and violations of IHL allegedly committed in the area.

In a joint statement, the UN Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide and the African Union (AU) Special Envoy on the Prevention of Genocide and Other Mass Atrocities warned of the real and growing risk of genocide in Sudan, stressing that the crimes committed display strong indicators of a deliberate intention to inflict conditions of life calculated to bring about the physical destruction, in whole or in part, of targeted communities.

During late October, the RSF also claimed to have captured the strategic town of Bara in North Kordofan, as well as the town of Umm Dam Haj Ahmed, northeast of the capital of North Kordofan, El Obeid. On 4 November OCHA reported that at least 40 civilians were killed in El Obeid during an attack on a funeral gathering.

Recent reports indicate a notable increase in SAF-run detention centers, with civilians increasingly targeted. The SAF has cracked down on mutual aid groups and arbitrarily detains people in inhumane conditions, causing severe physical and psychological harm to intimidate, coerce, punish or discriminate.

On 12 September the United States, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt – the Quad – presented a roadmap to end the conflict, proposing a three-month humanitarian truce, a permanent ceasefire and a nine-month civilian-led political transition. While the RSF announced on 6 November that it had agreed to the truce, there has been no sign of compliance. The plan has faced criticism for offering little assurance of a genuinely civilian-led transition, especially given the Quad members’ own involvement in the conflict.

ANALYSIS:

General Burhan and General Hemedti have consistently obstructed Sudan’s political transition to preserve and expand their power and privileges. Both continue to recruit forces along ethnic lines and strengthen relationships with regional powers, including several Gulf states.

While a ceasefire between the SAF and RSF is vital, it will not end the RSF’s ongoing identity-based violence. For decades, the Arab-dominated government imposed its control on ethnic minorities and exploited ethnic divisions, with armed Arab militias like the Janjaweed (the RSF’s forerunner) fueling deadly competition for resources and pastoral land. Civilians in Darfur, particularly non-Arab communities and populations in El Fasher, are at risk of ethnic cleansing and genocide given the region’s genocidal history, entrenched impunity for past crimes and ongoing ethnically charged violence.

Impunity has allowed those responsible for atrocity crimes and grave human rights violations to remain in leadership positions. During his dictatorship, former President Bashir, government officials and militia leaders were allegedly responsible for crimes against humanity, war crimes and acts of genocide, for which they were indicted by the International Criminal Court following a 2005 UNSC referral. As a commander of the Janjaweed, General Hemedti was also implicated in atrocities committed during the conflict in Darfur and beyond.

RISK ASSESSMENT:

-

-

- Escalating humanitarian and human rights catastrophes driven by intense armed conflict, with widespread violence in densely populated areas.

- Deliberate targeting of civilians based on their ethnicity, which may amount to ethnic cleansing and genocide.

- Past or present serious discriminatory practices, policies or legislation against marginalized communities and persons belonging to minority groups, some of which may amount to crimes against humanity and acts of genocide.

- Complete absence of meaningful reconciliation, accountability or transitional justice mechanisms, leaving victims and survivors without redress.

- Sustained external interference through the provision of arms, funding, logistics, training or other forms of support by states, private companies and other entities.

-

NECESSARY ACTION:

Generals Burhan and Hemedti must agree to a permanent cessation of hostilities and all forces under their command must adhere to IHRL and IHL. The international community, including the UNSC, AU and UN member states, must use diplomatic channels, far-reaching sanctions and public condemnation to pressure the SAF, RSF and allied militias to immediately cease hostilities and attacks against civilians, particularly in and around El Fasher. The UNSC must urgently consider adopting a strong resolution with effective measures to protect civilians and prevent further escalation, including expanding the sanctions regime to target those responsible for conflict-related sexual violence, ethnic-based attacks and other atrocities.

Alongside ceasefire negotiations, the international community must rigorously assess the risk of further atrocities by identifying communities at imminent risk and coordinating timely, context-specific responses. Given Sudan’s fragmented conflict, prevention and protection strategies must be tailored to local needs. Detailed mapping to identify acute risks are needed. The UN and member states must develop a comprehensive plan to address the humanitarian and protection needs of civilians, particularly women, children, internally displaced persons and minorities.

International donors must utilize more innovative and flexible ways for aid delivery across Sudan, including support for civilian-run Emergency Response Rooms, neighborhood communities and the disbursement of cash grants to empower local communities.

A comprehensive and inclusive political dialogue involving all relevant stakeholders, including civil society and marginalized groups, must be facilitated to address the root causes of the conflict and lay the groundwork for lasting peace.

For more on the Global Centre’s advocacy work on the situation in Sudan, see our Sudan country advocacy page.

Atrocity Alert No. 462: Sudan, Haiti and Mozambique

Related Content

Atrocity Alert No. 471: Sudan, Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory and Burkina Faso

Letter to UN Human Rights Council members on atrocity prevention priorities at the Council’s 61st session