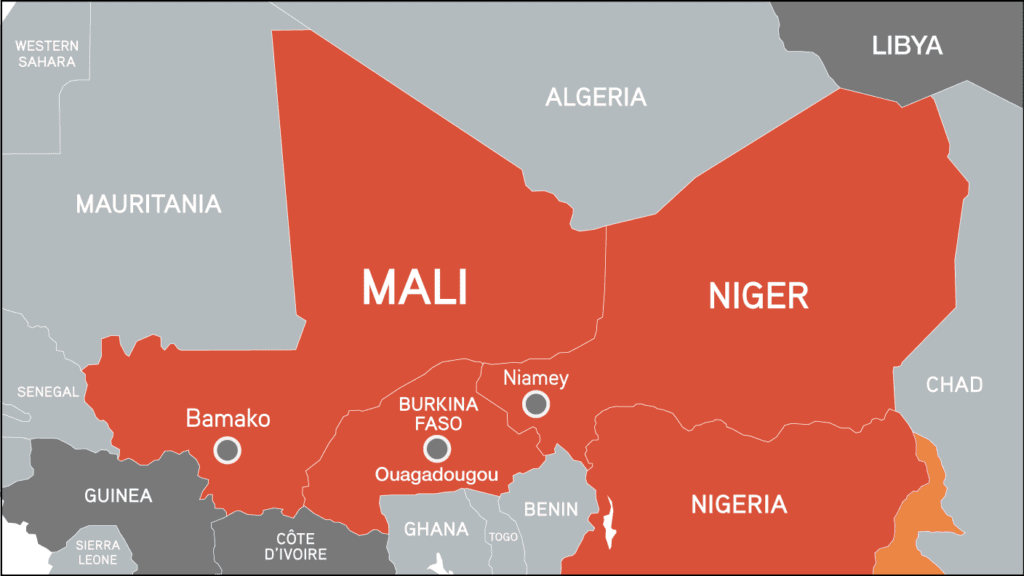

Central Sahel, Burkina Faso

Recurrent and expanding violence perpetrated by armed Islamist groups, as well as security operations to confront them, threaten populations in the Central Sahel – Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger – with violations that likely amount to crimes against humanity and war crimes.

BACKGROUND:

Populations in the Central Sahel – Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger – are enduring armed conflict and inter-communal violence amidst an entrenched insurgency driven by armed Islamist groups affiliated with al-Qaeda (JNIM) and the so-called Islamic State Sahel Province. At least 2.8 million people are internally displaced in the region, including 2.1 million in Burkina Faso alone. Violence has also taken place between rival ethnic militias and community-based self-defense groups resulting in reprisal attacks and countless abuses.

Armed Islamist groups perpetrate recurrent abuses and attacks against civilians. These groups systematically use sieges, threats, kidnappings, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and landmines as deliberate tactics of war as they seek to control supply routes and increase areas of influence. They have also enforced their own interpretation of Sharia law in areas under their control, imposing severe gender discriminatory rules. In besieged areas, armed Islamist groups are blocking humanitarian aid to civilians and causing starvation, imposing forced taxation and strategically destroying and looting civilian objects, including places of worship, health centers, food reserves and water services, among other violations of International Humanitarian Law (IHL). Insurgents also routinely perpetrate grave violations against children and target secular state education, burning schools and threatening, abducting or killing teachers.

Counterterrorism operations have often led to human rights violations in all three states, with security forces in Mali and Burkina Faso implicated in likely war crimes and crimes against humanity. The Malian Armed Forces (FAMa) and Russian paramilitary group Africa Corps (formerly the Wagner Group) have perpetrated possible war crimes and crimes against humanity, including summary executions, rape and sexual violence, pillaging and torture against civilians, since at least December 2021. An offensive by FAMa and paramilitaries in northern Mali has been characterized by systematic and indiscriminate killing of civilians – particularly Tuareg, Arabic-speaking tribes and Fulani – and indiscriminate airstrikes, among other abuses. State-sponsored militias in Burkina Faso, notably the Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP), have also been implicated in grave crimes along ethnic lines.

The insurgency in the Central Sahel has its origins in the 2012-2013 armed conflict in northern Mali, during which populations endured war crimes and crimes against humanity. The International Criminal Court (ICC) has subsequently issued an arrest warrant for Iyad Ag Ghaly, the head of the armed Islamist group Ansar Dine, for war crimes and crimes against humanity. The ICC has convicted Al Hassan Ag Abdoul Aziz, a senior member of the Islamic Police of Timbuktu and Ansar Dine, of war crimes and crimes against humanity, while Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi was convicted of war crimes for the intentional destruction of cultural sites. Accountability remains limited with few alleged perpetrators having been arrested, prosecuted or tried for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The region has faced significant political and security upheaval since 2020, including military takeovers in all three countries. Amid these shifts, the military regimes have taken several measures to repress civic and political space and reduce international scrutiny into the country’s human rights situations. In Burkina Faso, the “general mobilization” decree – a law purportedly aiming to curtail the spread of violence and recapture territory – has been abused by the authorities through forcible conscription, arbitrary arrests or kidnapping of dozens of perceived critics, human rights defenders and magistrates in counterinsurgency operations, likely amounting to enforced disappearances. The decision by the three military regimes to create the Alliance of Sahel States – a mutual defense pact – and formally withdraw from the Economic Community of West African States on 29 January 2025 has compounded regional fragmentation and tensions.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS:

In Burkina Faso, JNIM has perpetrated a string of attacks in at least four localities in the north and east of the country throughout February, causing an unknown civilian death toll. In the Bandiagara region of Mali, JNIM has burned homes, looted livestock and launched attacks against civilians in recent months in apparent retaliation against local communities whom JNIM accuses of collaborating with the Dan Na Ambassagou self-defense militia. In northeastern Mali, a suspected armed Islamist group attacked a civilian convoy escorted by FAMa and allied militias during February, killing at least 34 civilians and injuring 34 others. Residents told Human Rights Watch that attacks on civilians along this road became so frequent that military authorities in Gao have imposed armed escorts since late 2024. Southwest Niger’s Tillabéri region has faced recurrent attacks by armed groups, with a significant spike in violence during December.

Meanwhile, national security forces throughout the region have responded to the escalating insurgent activity with retaliatory violence against civilians. According to local sources, in late January 2025 FAMa and Dozo militia men reportedly killed at least 20 civilians and destroyed civilian property during a string of attacks in several villages in Ségou, Mali. In February the Malian government announced an investigation into allegations of FAMa and mercenaries summarily executing civilians in Gao. In Burkina Faso, reports emerged incriminating Burkinabè soldiers in massacres on 28 January in the northeast of the country.

In February the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention demanded the immediate release of former Nigerien President Mohamed Bazoum and his wife – who have been detained since the military coup in July 2023 – and determined that their detention is arbitrary and violates international law.

ANALYSIS:

While Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger each face distinct challenges, these states also share a legacy of structural vulnerabilities, weak governance, limited state presence and porous borders. Although the military authorities in each country have expressed a goal of advancing security to protect civilian lives, the security situation has continued to deteriorate, amplifying risks to civilians. While the FAMa has a record of human rights violations, the scale of crimes has increased since the deployment of Russian paramilitaries.

The expanded area of influence and/or control by armed Islamist groups has resulted in serious human rights abuses and war crimes. Armed Islamist groups appear to be deliberately targeting civilians as a tactic to pressure communities into cooperation, as well as utilizing blockades to punish communities perceived to be supportive of the military. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data, these groups are increasing community outreach and preaching efforts to present themselves as “protectors” in attempts to consolidate their influence over the civilian population.

Populations continue to be targeted and persecuted on the basis of their ethnic and/or religious identity. The VDP’s actions fuel abuses and possible atrocity crimes, aggravate ethnic tensions, encourage militant recruitment among pastoralists and contribute to prevailing impunity. The growing use of air and drone strikes, IED attacks, rocket and mortar shellings underscore a shift in combat tactics and has contributed to indiscriminate violence, civilian harm and possible war crimes.

Despite the deterioration of the situation in Mali, the UN sanctions regime and peacekeeping mission were terminated, resulting in significant gaps in human rights monitoring, civilian protection and accountability. The crackdown against human rights defenders and civic space across the three countries has inhibited independent documentation and monitoring of violations and abuses. Other efforts to investigate allegations of atrocities by state actors have also been undermined.

RISK ASSESSMENT:

-

- Militarized approach of counterinsurgency that stigmatizes certain populations and increases risk of escalatory dynamics.

- Unresolved long-standing inter-communal tensions and grievances and the use of militias and self-defense groups that perpetrate attacks along ethnic lines.

- Impunity for past and ongoing atrocities by all armed actors.

- Capacity to commit atrocity crimes, including availability of personnel, arms and ammunition.

- Closure of civic space and intensified repression against real or perceived dissenting voices.

NECESSARY ACTION:

While countering violent extremism remains crucial, it is essential that all armed actors ensure that their operations comply with IHL and do not exacerbate inter-communal tensions or fuel further violence. The militaries must establish guidelines on the use of aerial weapons during operations and ensure they minimize civilian harm. All actors should refrain from supporting or collaborating with ethnically aligned militias with poor human rights records.

Additional measures must be implemented to end the proliferation of arms, improve land management and reach political settlements in areas where atrocity risks are greatest.

The military authorities of the Central Sahel – with support from national human rights commissions and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights – should investigate all violations of International Human Rights Law and IHL. Authorities must stop harassing civil society and ensure they can operate without fear of reprisals. The Malian military government should cooperate with the UN Independent Expert on the situation of human rights in Mali to ensure they can effectively carry out their mandate.

Atrocity Alert No. 433: Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Myanmar (Burma) and Mali

Related Content

Atrocity Alert No. 438: Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Mali and Myanmar (Burma)

Atrocity Alert No. 433: Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Myanmar (Burma) and Mali