From Non-Intervention to Non-Indifference: The Responsibility to Protect, the United Nations and the Prevention of Genocide

On 31 March, Global Centre Executive Director, Simon Adams, delivered the following speech at the International Conference on Genocide Prevention, held in Brussels.

Thank you to the organizers.

I’m honored to be here in Belgium at this esteemed event. After careful planning, almost exactly 20 years ago, on 7 April 1994 Rwanda’s genocide began. Over the following 100 days almost a million human beings were systematically murdered at roadblocks, in the streets and even in churches where thousands sought sanctuary.

There were no death camps or gas chambers. This was a sickeningly efficient genocide carried out mainly with farm implements in a remote corner of Africa that no one cared about.

In the years after the genocide, I worked for a while as part of a civil-society program that brought youth from other conflicts to Rwanda so that they could meet face-to-face with genocide survivors, and with some genocidaire, and try to understand better how the seeds of genocide were carefully harvested in that country.

My work took me to many massacre sites, including the École Technique Officielle, on the outskirts of Kigali. The last time I was there they were exhuming the hastily constructed mass graves.

I stood watching for a while as they sorted the bones of the dead. They were stacking thousands of femurs, collar bones. Massive piles of death. Every bone, every skull, every severed limb was an indictment of the international community and its failure to adequately respond.

I say this because Rwanda still haunts any discussion of the prevention of genocide in our times.

The Responsibility to Protect (R2P)

Having presided over two of the greatest failures in the history of UN peacekeeping (Rwanda in 1994 and Srebrenica in 1995), Kofi Annan was looking to make amends after he became UN Secretary-General in 1997.

So in 2000 – at the start of the new millennium, Kofi Annan posed the question very sharply and directly. “If humanitarian intervention is, indeed, an unacceptable assault on sovereignty, how should we respond to a Rwanda, to a Srebrenica, to gross and systematic violations of human rights that offend every precept of our common humanity?”

Prompted by Annan and funded by the Canadian government, in 2001 the ICISS commission led by Gareth Evans and Mohammad Sahnoun developed the concept of “the Responsibility to Protect” (widely known by its abbreviation ‘R2P’).

The Responsibility to Protect focused exclusively on 4 atrocity crimes and 3 pillars. The 4 crimes (three are legally defined in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court) – genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity.

- primary responsibility of state to protect its populations

- responsibility of international community to assist

- Coercive measures if a state is manifestly failing or unwilling to uphold its responsibility to protect.

The Responsibility to Protect was unanimously adopted at the 2005 UN World Summit – the largest assembly of heads of state and government in history.

Africa Origins

But much of the momentum around R2P was created in Africa. This is often not recognized. For example, when the African Union proclaimed its Constitutive Act in July 2000, article 4(H) boldly declared a shift from the politics of nonintervention to the politics of non-indifference with regard to mass atrocity crimes on the continent.

The impact this had on policymakers and opinion shapers outside of Africa is often underestimated.

The UN is built around the principle of sovereign equality – the idea that all states have the right to determine their own affairs within their own borders. Furthermore, they have a right to territorial integrity (ie: not to be invaded) and this is enshrined in Article 2(7) of the UN Charter.

However, it is a bitter irony that the walls of national sovereignty, designed to protect small countries from conquest, have sometimes been misused by a dwindling number of governments who still view sovereignty as a license to kill.

The Responsibility to Protect recognized that the world has changed and while the UN was established to stop conflicts between states, most conflicts are now within national borders.

So how to harmonise this unequal marriage between national sovereignty and international obligation (as represented in Universal Declaration of Human Rights)?

The Responsibility to Protect is predicated upon the notion that sovereignty entails responsibility. (This is, again, largely an African concept in origin, drawing on the ideas of Francis Deng, previously the UN Secretary-General’s Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide, and now South Sudan’s leading diplomat at the UN).

This takes the question of rights away from potential interveners, and places it where it belongs – the right of vulnerable people to protection.

And so as Ramesh Thakur has written, the underlying premise of the Responsibility to Protect is a fundamental rejection of both “unilateral interference and institutionalized indifference”.

Progress and Setbacks

In the 8 years since R2P was unanimously adopted we have made genuine progress. R2P played an important role in framing the international community’s response (led by Kofi Annan and his team) to the crisis in Kenya in 2007-2008. It played a decisive role in Cote d’ Ivoire and Libya in 2011. It continues to play a role in a range of situations where coercive measures are not, thankfully, necessary.

But the development of R2P has not been without tragic disappointments and setbacks.

Libya and Syria have provided R2P’s biggest challenges to date. Although there have also been very divisive debates about R2P with regard to Sri Lanka and elsewhere.

These cases are difficult precisely because they raise issues of accountability and coercion to halt mass atrocities – matters the UN Security Council has always struggled to address with undeviating and proximate determination.

Post-Libya controversies re: R2P have tended to focus upon the use of military force, but of course R2P – and this has been crucial to its international acceptance – is about much more than that.

Prevention and R2P Focal Points

Running right through all three pillars of R2P is an absolute commitment to prevention:

-

-

- prevention of initial outbreak of a crisis;

- prevention of its escalation;

- and prevention of recurrence.

-

R2P is concerned with the prevention of mass atrocity crimes, not the outcome of elections. But in Kenya in 2013, R2P offered an analytical lens to understand the nature of threat facing the country, while also providing a tool for mobilizing preventive action.

Kenya also reminds us that while both governments and civil society talk endlessly about the importance of prevention, it is the part of R2P that we understand the least.

And as recent debates at the HRC in Geneva have shown, debates around early warning and/or accountability for past atrocities (Burma/Myanmar and Sri Lanka spring to mind) can also be fractured and controversial.

But partly to address this preventive deficit, in 2010 the governments of Australia, Costa Rica, Denmark and Ghana embarked upon the R2P Focal Points initiative.

A R2P Focal Point is a senior government official responsible for the promotion of mass atrocity prevention (incl the prevention of genocide) at the national level.

The third annual meeting of the Global Network of R2P Focal Points was held during June 2013 in Accra, Ghana. More than thirty-five countries and three regional organizations attended.

The meeting was notable for the extent to which appointed R2P Focal Points were able to share direct experience regarding the practicalities of mass atrocity prevention. Pragmatic lessons from peacekeeping operations, or regarding security sector reform or curtailing hate speech were discussed at length, including by representatives of states still emerging from conflict.

Altogether, since September 2010, 37 countries, representing both the global north and south, have appointed a national R2P Focal Point. These states are actively building a “community of commitment” that increases our international capacity to prevent mass atrocities, including genocide.

It brings together states as diverse as the DRCongo and the United States, Guatemala and Cote d’Ivoire, Australia and Bosnia. Such a network for prevention would have been politically inconceivable only a few years ago.

The UNSC & R2P beyond Syria

But what about when prevention fails? Even in the toughest case – with the Security Council deeply divided over Syria (and action blocked by the vetoes of Russia and China) – individual states and regional organizations took action to uphold their Responsibility to Protect.

By March 2012, one year after the current conflict began, at least 49 countries and the Arab League had already diplomatically isolated the Syria govt and imposed targeted sanctions.

Other parts of the UN system also lived up to their responsibilities. The Human Rights Council in Geneva, for example, passed no less than eleven resolutions condemning mass atrocities in Syria between 2011 and the end of 2013 and established an independent International Commission of Inquiry.

Similarly, the UN General Assembly has passed at least seven resolutions condemning atrocities in Syria.

But unfortunately, unlike UN Security Council resolutions, Human Rights Council and General Assembly resolutions are not binding under international law. And so the civil war grinds on, consuming more than 140,000 lives and inspiring perpetrators on both sides to commit new and appalling atrocities.

We will never know what might have happened had the Security Council sent a clear message to both the Assad government and armed rebels in late 2011 that the international community was united in opposition to mass atrocity crimes.

What we do know is that the absence of timely and decisive action directly contributed to the sectarian civil war that now endangers the lives of millions of civilians across the Middle East.

This is just one of the reasons why the Global Centre for R2P (and some other civil society partners) are working with the French government and with the ACT group at the UN, to push for voluntary restraint on the use of the veto in mass atrocity situations. We believe that the permanent members of the Council have a responsibility not to veto when faced with these most conscience-shocking crimes.

This is an issue that will not go away, no matter how much some permanent members of the UNSC would like it to.

R2P beyond Syria

It is also worth remembering that while sections of the media predicted that Libya and Syria would be the graveyard of R2P as an emerging international norm, the facts indicated otherwise.

In the five years prior to the Libya intervention in March 2011 the Security Council had passed only four resolutions which referenced R2P – two were thematic resolutions on the protection of civilians, the other two concerned crises in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Darfur, Sudan.

By contrast, in the 3 years since resolution 1973 of March 2011, which authorized the civilian protection operation in Libya, the Security Council has passed 14 resolutions that directly reference R2P.

One of these concerned the trade of small and light weapons, while the others adopted measures to confront the threat of mass atrocities in Cote d’Ivoire, Yemen, Mali, Sudan and South Sudan, and Central African Republic.

It is also worth keeping in mind that 8 out of 15 current UN peacekeeping operations have a R2P and/or protection of civilians, mandate.

Together they prove that, to paraphrase Mark Twain, rumours of R2P’s normative death inside the Security Council were greatly exaggerated. On the contrary, R2P is framing meaningful attempts to save lives.

The 20 year Test

R2P has been described by the former UN Special Adviser on the Responsibility to Protect Dr. Edward Luck as the fastest developing international norm in history. At a meeting we both attended at the British Houses of Parliament, Dr. Luck compared the trajectory of R2P since 2005 to the evolution of human rights norms after World War II.

Despite the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the human rights situation in much of the world was still wretched during the 1950s as Cold War hypocrisies plagued the international system. Human rights terminology was worn thin by opportunistic misuse.

It is only from the vantage point of a new century that we can look back and proclaim that despite this, human rights still made gradual, but cumulative, normative progress over the second half of the twentieth century.

The underlying ideas were not fatally weakened by inconsistent application. The enduring challenge was to work towards universal application.

Less than a decade after R2P appeared in paragraphs 138 and 139 of the World Summit Outcome Document, it is difficult to get a precise measurement of R2P’s success.

But we have won the battle of ideas. Within the UN the debate now is about how R2P should be meaningfully implemented in specific cases, not whether such a responsibility exists.

The central challenge remains – to strengthen the politics of non-indifference.

Right now there are people in Darfur or South Kordofan in Sudan, in the Kivus in DRCongo, Rohingya Muslims in Burma, and people elsewhere who are continuing to face the reality of mass atrocity crimes.

Despite progress, our ability to respond adequately is still fundamentally a question of political will.

For example, compare and contrast the cases of South Sudan and Central African Republic. We have been warning of the rising threat of mass atrocity crimes and civil war in both countries for roughly the same time (ie: since early 2013).

We had plenty of early warning. But when the crises in each country degenerated into widespread mass atrocity crimes on 5 December (in case of CAR) and 15 December (in case of South Sudan), the international response was not the same.

The world responded, invoking R2P, in both cases. But financial constraints, emotional investment and geo-politics affected the nature, intensity, urgency and depth of the response.

In South Sudan the UN has played an important role in saving lives. Three peacekeepers were killed, and over 75,000 civilians are still sheltering in UN bases. The Council moved quickly to refocus the UN Mission on a primary role of civilian protection.

Meanwhile the crisis in neighboring Central African Republic is equally grave and disturbing. Unlike South Sudan, the international NGO community was comparatively thin on the ground. Moreover, no major international power had a strong geopolitical interest in CAR. But consistent advocacy at the UN and in Paris influenced the French government to intervene in support of the AU mission in CAR.

This civilian protection operation is happening under an R2P mandate and is desperately trying to deal with a situation that contains within it, to quote UN Special Advisor Adama Dieng, the potential “seeds of genocide”.

Since 5 December the French have lost 3 soldiers in CAR and the AU force has lost 21 men. And yet they have stayed.

But despite the mounting horror in CAR, we are still struggling to get approval for a UN peacekeeping operation. The opposition appears at times, alas, to be more about dollars and cents, than about lives.

So the lesson in both CAR and South Sudan is that we still struggle to close the gap between words and deeds. Pretty words don’t save lives, but timely action can.

Still, we should remember that in South Sudan or Central African Republic, R2P is actually making a difference to those who might otherwise be marked for death. And to quote my colleague Tom Weiss, there is now “the doublestandard of inconsistency whereas formerly there had been only a single standard: do nothing.”

Civil Society

What is the role of civil society in all of this? I would like to think that over the last 20 years there has been a massive expansion of credible and professional civil society organizations who are actively engaged with policymaking are often at the frontlines where civilians are most threatened. The media can also play an important role. But I will leave it to our three speakers to elaborate in more detail on the civil society dimension.

Conclusion

I think the Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon’s words re: R2P are especially relevant: “I would far prefer the growing pains of an idea whose time has come to sterile debates about principles that are never put into practice.”

Twenty years after Rwanda we are reminded that where ever and when ever people are targeted for their religion (or lack thereof); for their ethnicity or race; for their sexual orientation or political allegiances; then one hears, not only the deadly echo of the past, but a disturbing portent of the future.

We see in the Central African Republic and several other situations today, the incipient “seeds of genocide.” But seeds don’t always grow. Raphael Lemkin gave the crime a name, but he left it to us to figure out how to prevent it.

Which is why when it comes to stopping genocide and other mass atrocity crimes in the twenty-first century I believe that the Responsibility to Protect is still the best instrument we have to bridge the gap between the noble aims of the UN, and the imperfect, cynical world of global governance.

I thank you.

Related Content

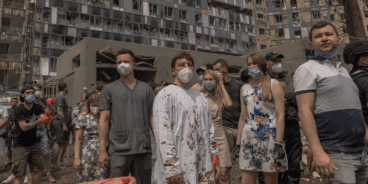

Atrocity Alert No. 402: Ukraine, Myanmar (Burma) and Nigeria