Recommendations for the 41st Session of the Universal Periodic Review

Your Excellency,

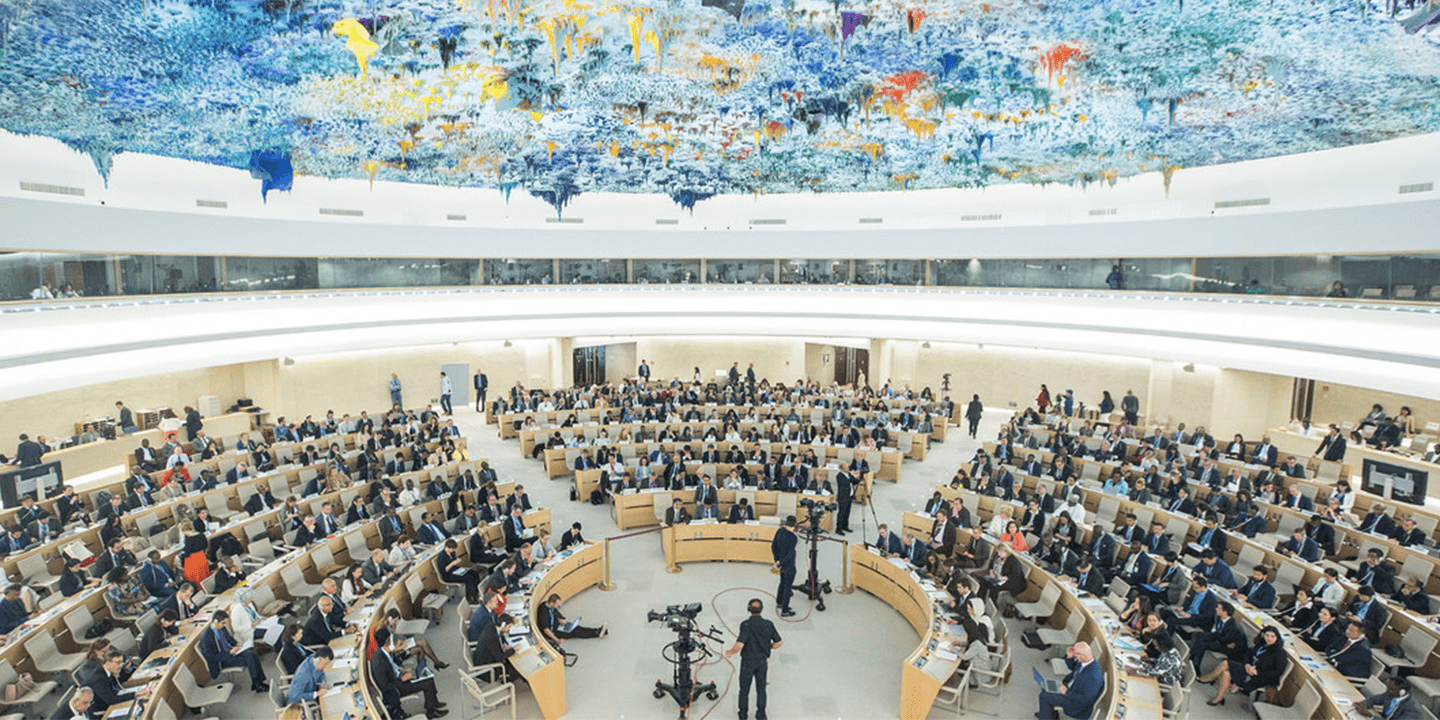

In 2005 heads of state and government unanimously agreed on the responsibility of states to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. Under the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), it is the primary responsibility of each individual state to protect their own population and the responsibility of the international community to assist them in doing so. The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) can play an important role in assessing each country’s institutional preparedness to protect human rights and prevent mass atrocities. During the 41st session of the UPR working group, the Global Centre encouraged member states to provide all those under review with the following recommendations, where applicable:

-

-

- Expeditiously appoint an R2P Focal Point – a senior level government official responsible for the promotion of mass atrocity prevention at the national, regional and international level;

- Sign, ratify and implement the core instruments of International Human Rights Law (IHRL) and International Humanitarian Law (IHL), including the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Additional Protocols I and II to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, the Arms Trade Treaty, and 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict;

- In keeping with R2P’s Pillar II, request support from other states, as well as regional and international organizations, when risks exist that cannot be addressed by your government alone;

- Ensure that all national security forces respect human rights and IHL and fulfill their responsibility to protect all populations within the territory of your state, regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation or any other status;

- Support accountability for atrocity crimes and all relevant institutions of international justice;

- Issue open invitations to HRC-mandated Special Procedures and fully cooperate with all other HRC mechanisms and procedures;

- Protect human rights defenders and the media, as well as the rights of civil society to operate freely, safely and independently.

-

In addition to these general recommendations, the Global Centre provided tailored recommendations provided below for India, Indonesia and the Philippines.

India

Under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the government of India has intensified its systematic discrimination against the Muslim minority population by imposing Hindu nationalist policies since the BJP came to power in 2014. These policies include voter suppression measures against Muslims and Dalits and the expulsion and detention of Muslim Indians, which the government calls “illegal infiltrators.” The BJP’s exclusionary and nationalist ideology portrays India’s Muslim minority population as a growing threat and leaves marginalized groups at increased risk of discrimination and violence.

While anti-Muslim rhetoric has been prominent in speeches made by various BJP politicians since they came to power, it intensified following protests in 2019 against the Citizenship Amendment Act, which outlines a path to citizenship for non-Muslim immigrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Hate speech, including calls for Hindus to arm themselves and kill Muslims in the country, has proliferated and heightened the risk for atrocities. For example, a speech by a BJP politician in February 2020 triggered India’s worst sectarian violence in recent years, when at least 45 people were killed and more than 300 injured as a result of rioting and attacks by Hindu nationalist mobs in New Delhi.

India has a long history of inter-communal violence and attacks on minority religious populations, with widespread attacks on Muslims in Gujarat state in 2002 and against Sikhs in Delhi in 1984. Anti-Muslim violence has risen significantly under the Modi administration since 2014, with frequent reports of Hindu mobs attacking Muslims and authorities in states ruled by the BJP increasingly using abusive punishments against Muslims deemed to have violated the law. Authorities have also demolished Muslim homes and properties without legal authorization. In June 2022 the UN Special Rapporteurs on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living; on minority issues; and on freedom of religion or belief issued a joint statement alerting that, “some of these evictions have been carried out as a form of collective and arbitrary punishment against the Muslim minority and low-income communities for alleged participation in inter-communal violence.” Other religious minority groups, including Dalits and Christians, also face discrimination and violence based on their identity. The government’s failure or unwillingness to hold perpetrators accountable for violence and persecution against religious minorities and other marginalized groups may encourage further targeted attacks and harassment.

Meanwhile, risks in the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir have also heightened following India’s revocation of the region’s special status in 2019. Subsequent protests inside Kashmir and around the country were met with repression and the government did not effectively prosecute those responsible for violence against protesters. The UN Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict found in its June 2022 report that Indian security forces have also detained children and used torture against children in Jammu and Kashmir.

The Global Centre urged member states to include the following recommendations to India during the UPR session on 10 November:

-

-

- Cease targeted violence, intimidation and persecution of religious minority groups, particularly Muslims, Dalits and Christians, as well as human rights defenders and government critics;

- Immediately end discriminatory and exclusionary rhetoric and ideology that may incite violence and hostilities against vulnerable minority groups, rigorously enforce domestic hate speech laws – which prohibit hate speech that targets people on the basis of their race, religion or caste – and take disciplinary action against any BJP official responsible for inciting violence;

- Thoroughly and independently investigate all attacks on religious minority groups and other vulnerable populations and prosecute those responsible to contribute to the deterrence of further attacks;

- Adopt a comprehensive national plan that addresses the risk of mass atrocities, in particular by reforming its anti-minority policies and combatting the proliferation of hate speech and incitement to violence and discrimination;

- Abide by its obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which prohibits discrimination on any ground and obligates states to ensure that everyone is equal before the law and to ensure equal protection of the law.

-

The Global Centre further encouraged member states to consider the following advanced questions for the review of India:

-

-

- What steps will the BJP take to prevent an escalation of violence and harassment against religious minority communities and other vulnerable groups in the lead up to the May 2024 national parliamentary elections?

- How will the government ensure credible and transparent investigations into human rights violations, including of the police and BJP-affiliated paramilitary armed groups?

-

Indonesia (Papua/West Papua)

For the last fifty years indigenous Papuan populations have suffered under Indonesian military rule in West Papua. After the fall of the New Order regime in 1998, the Indonesian government responded to demands to realize the West Papuan right to self-determination via a 2001 Special Autonomy law, under which the provincial government gained autonomy in all matters except defense, international relations, fiscal and monetary policy, religion, law and justice. The Special Autonomy arrangements have been highly contested by indigenous communities in Papua and West Papua as the special protections awarded to indigenous groups are often ignored or overruled by conflicting legislation. Restrictions on autonomy have fueled ongoing pro-independence political resistance and armed rebellion, as well as government repression.

A 2021 amendment to the Special Autonomy law, implemented without consultation of indigenous Papuan groups, ignored long-standing demands regarding Indonesian migration, distribution of resources and the protection of human rights while shrinking the power of representative institutions for indigenous Papuans and enabling the commission of human rights violations. On 22 February 2021 at least 1,000 indigenous People of Dogiyai Regency organized a peaceful protest in response to the amendment, as well as the proposed expansion of Papua province and development of a new Indonesian National Police Station (Polres). Similar demonstrations have been organized in other cities and regions, including Jakarta and Malang, since February 2021.

These protests were met with disproportionate intervention by Indonesian security forces. Between April and November 2021 the UN received reports of extrajudicial killings, including of young children, enforced disappearance, torture and inhuman treatment and the forced displacement of at least 5,000 indigenous Papuans by Indonesian security forces. The increase in civil unrest triggered a new onset of pro-independence protests in March 2022, increasing the risk of a more severe response by the Indonesian government.

Meanwhile, since 2018 the Papua province has become increasingly militarized as Indonesian security forces respond to attacks by the West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB) and other rebel groups. In December 2018 an escalation between state forces and TPNPB displaced between 60,000 to 100,000 people. From August to September 2019 tensions between Indonesian migrants and indigenous Papuans intensified as a result of demonstrations condemning racism and demanding the realization of the West Papuan people’s right to self-determination. In response, more troops were deployed to the region. The troops subsequently harassed and intimidated protesters, as well as arbitrarily arrested activists and human rights defenders.

Indigenous Papuans have been systemically denied their basic human rights, including the right to self-determination. The revision of the Special Autonomy Law has unilaterally challenged the spirit of the law and disregards the right of free, prior and informed consent, as well as the right to political participation of the indigenous people of West Papua. Populations in Papua and West Papua remain at risk of possible atrocity crimes due to ongoing clashes between Indonesian security forces and Papuan militia groups, increasing inter-communal tension within indigenous Papuan groups, and competition between indigenous Papuans and Indonesian migrants.

The Global Centre urged member states to include the following recommendations to Indonesia during the UPR session on 9 November:

-

-

- Promptly initiate independent, impartial and transparent investigations into potential systematic violations and abuses of human rights, such as torture, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings of Papuans by security forces, including at the highest level;

- Improve freedom of information and monitoring of potential abuses by ensuring national and foreign journalists, researchers and civil society activists have unrestricted access to Papua and West Papua;

- Cooperate with UN human rights mechanisms by extending an invitation to the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples to visit Indonesia, including Papua, in line with Indonesia’s indication of openness to collaborate with Special Procedures mandate holders;

- Implement comprehensive human rights trainings for security forces operating in the Papua region that emphasize nonviolent strategies to better address Papuan grievances and alleviate drivers of conflict without a heavy-handed military response.

-

The Global Centre further encouraged member states to consider the following advanced questions for the review of Indonesia:

-

-

- What steps has the government taken to engage in dialogue with pro-independence Papuans regarding the 2021 extension of the Special Autonomy Law and its implications on atrocity risks faced by indigenous Papuans?

- Has the Indonesian military made any progress on the recent commitment to shift from a combat-heavy approach to a humanistic approach in the Papua region?

- What steps has the government taken to engage with pro-independence militias toward the goal of disarmament and peaceful resolution?

-

Philippines

During the June 2016 – June 2022 presidency of Rodrigo Duterte, thousands of people were extrajudicially killed in the Philippines during a so-called “war on drugs.” According to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), at least 8,660 people have been killed since July 2016 in police operations and by unidentified gunman carrying out vigilante-style executions of alleged drug offenders, with thousands of deaths still under investigation. Local human rights groups, including the government appointed Philippines Commission on Human Rights, indicate that the number could be more than triple the official figure. Government officials have repeatedly dismissed calls for impartial investigations, with the former Justice Secretary, Mr. Vitaliano Aguirre II, stating that the extrajudicial killings could not amount to crimes against humanity as drug offenders are “not part of humanity.”

Following a resolution adopted by the HRC in 2020, a three-year Philippine-UN Joint Program was established to institutionalize human rights and provide technical training and capacity building. Unfortunately, the Philippine government has stalled its work, blocking progress. On 4 June 2020 OHCHR released a report on the human rights situation in the Philippines, focused primarily on the period from 2015-2020. The report found systematic and long-standing human rights abuses committed by the government, including killings and arbitrary detentions during the “war on drugs.” The report also found evidence of at least 248 targeted killings of journalists and human rights defenders. In their final report on 6 September 2022, the High Commissioner for Human Rights stated the Philippine government had taken some steps to pursue accountability for human rights violations and abuses, but access to justice for many victims remained out of reach due to limitations in investigative capacity, lack of cooperation between agencies and protracted judicial processes. Victims and their families have also faced fears of reprisal attacks for seeking justice.

Despite a transition of power to the current President, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., on 30 June, killings and abuses against human rights defenders and others continue. From July to October “Dahas” – a project run by the Third World Studies Center at the University of the Philippines – reported at least 90 drug-related deaths and the deaths of two journalists.

Following a preliminary examination by former Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Fatou Bensouda, on 15 September 2021 the ICC opened a formal investigation into allegations of crimes against humanity committed between 1 November 2011 and 16 March 2019 – the end date of the Court’s jurisdiction in the Philippines.

Populations in the Philippines, particularly those suspected of drug-related activity, those working in human rights fields, or those critical of the government, face continued risk of targeted killings by government officials and armed vigilantes. The Global Centre urged member states to include the following recommendations to the Philippines during the UPR session on 14 November:

-

-

- Immediately end the campaign of extrajudicial killings, which may amount to crimes against humanity under international law;

- Conduct an independent and impartial inquiry into all enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings to ensure that the perpetrators of these crimes are brought to justice;

- Ensure the full cooperation with the ongoing work of the ICC on drug-related killings in the Philippines;

- Ensure human rights training for state security forces to enhance their capacity to protect human rights;

- Allow access to the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions.

-

The Global Centre further encouraged member states to consider the following advanced questions for the review of the Philippines:

-

-

- What progress has the Philippine government made on ensuring accountability for the thousands of extrajudicial killings since 2016?

- How does the Philippine government plan to integrate human rights training, including on IHL, IHRL and the commission of mass atrocity crimes, into its domestic police and military recruitment processes?

-

Related Content

Joint recommendations for the Universal Periodic Review of Yemen