The Responsibility to Protect: Can We Prevent Mass Atrocities Without Making the Same Mistakes?

The article below was written by Jaclyn Streitfeld-Hall and published in CIVICUS’ 2014 State of Civil Society, Reimagining Global Governance Report.

During the 2005 United Nations (UN) World Summit, member states agreed that they have a Responsibility to Protect (R2P) populations from four mass atrocity crimes: genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. In his first annual report on R2P in 2009, entitled “Implementing the Responsibility to Protect,” the UN SecretaryGeneral, Ban Ki-Moon outlined a three-pillar approach for the operationalisation of R2P. Pillar I notes that every state has the primary Responsibility to Protect its populations from the four crimes. Pillar II asserts that the wider international community should assist states in meeting this responsibility. Pillar III holds that if a state is manifestly failing to protect its population, the international community must be prepared to take appropriate collective action in a timely and decisive manner, in accordance with the UN Charter. Recent and ongoing crises have caused policy makers and analysts to question whether R2P has failed to achieve the promise of “Never Again.” While the response to the 2011 crisis in Libya, which resulted in an intervention and subsequent change of government, was swift and decisive, it resurrected criticism of humanitarian intervention as a violation of state sovereignty and a tool for influencing regime change. In contrast, subsequent diplomatic stalemates, particularly those within the UN Security Council regarding a response to Syria, have left many wondering if R2P fails to solve the problems of political will that allowed the international community to ignore the genocides in Rwanda and Srebrenica. Nevertheless, developments at the international, regional and domestic level over the past five years have shown that political actors are making critical steps towards engaging in mass atrocity prevention and assuring that the mistakes of previous devastating crises are not repeated.

R2P post-Libya

In February 2011, Libyan leader Muammar al-Qaddafi started a violent crackdown against anti-government demonstrations, resulting in the death of hundreds of protestors. In response, on 26 February the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1970, explicitly invoking the “Libyan authorities’ responsibility to protect its population.” After the threats to the population increased, the Council authorised a response using “all necessary measures” to protect the civilian population while repeating its call for the Libyan authorities to uphold their responsibility.

Many viewed the aftermath of Libya — and the resulting increased sensitivities around intervention and Pillar III response, R2P’s “most controversial” pillar — as a barrier to its normative progression. However, Libya was not the death sentence for R2P that some suspected it would be. In fact, in many ways it broadened momentum within the Security Council. By setting a precedent in using R2P language in the Libya resolution, the Council paved the way for the label to be applied to more situations with mass atrocity concerns. Even as new crises have evolved, the Council has made swift decisions, some of which referred directly to R2P, on situations in South Sudan, Mali, Yemen and Central African Republic. In South Sudan, for example, when evidence of mass atrocities emerged following a conflict that started on 15 December 2013, by 24 December the Council adopted a resolution expanding the number of peacekeepers deployed to the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), which operates under a mandate informed by R2P.

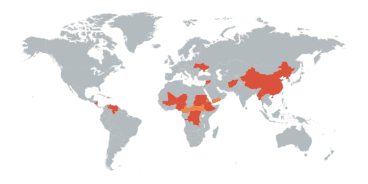

Since Resolution 1970 on Libya, the Council has passed 13 Resolutions and issued four Presidential Statements invoking the Responsibility to Protect. In 2013, two important developments facilitated this momentum. First, the membership of the Council has included a record number of states, 10 in both 2013 and 2014, who participate in the Group of Friends of R2P, an informal cross-regional group of states committed to advancing R2P at the UN that currently has 44 members. Efforts at developing a code of conduct for the Security Council that would potentially include a restraint on the use of the veto in mass atrocity situations also gained momentum when the French Foreign Minister, Laurent Fabius, published an op-ed in The New York Times indicating France’s support for such a measure.

A focus on prevention

Perhaps the most critical development in ensuring that R2P changes the way we eradicate atrocities has been a heightened emphasis on prevention. In contrast with previous methods of confronting atrocities, including humanitarian intervention, R2P was not envisioned merely as an international response to ongoing crises or a new means of generating political will to respond to early warning signs of mass atrocities. What Pillars I and II bring to the approach to mass atrocities is the perspective that states and other actors can and should be developing mechanisms that prevent atrocities before signs of crisis emerge.

Not only did R2P endure through the controversy surrounding Libya, but the resulting momentum to shift the dialogue away from Pillar III also had the effect of bolstering actions to implement atrocity prevention at home. As proponents of R2P began highlighting the more widespread acceptance of Pillars I and II, states started to critically look inward at their own domestic capacity to uphold their responsibility. In addition, conversations about international interactions shifted from focusing only on intervention to addressing the mechanisms through which states can assist each other prior to the outbreak of a conflict.

Some states have also started taking a whole-of-government approach to atrocity prevention. Rather than looking at conflict prevention mechanisms in isolation, states are asking themselves how everything from the development agenda to education can address mass atrocities. One of many examples of this is the United States’ Atrocities Prevention Board, which was designed to assess the government’s capacity to prevent mass atrocities at home and abroad and includes representatives from more than a dozen governmental agencies.

Governments have also started working more closely on joint efforts at mass atrocity prevention — thinking about how they can translate the tools that others states have used to their own national contexts. As a result, several networks of states have emerged at both the regional and global level to normalise conversations regarding the tools of prevention. These networks include the Global Network of R2P Focal Points, the Latin American Network for Genocide and Mass Atrocity Prevention and the joint platform for Global Action Against Mass Atrocity Crimes. The Global Network of R2P Focal Points, for which the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect serves as the secretariat, includes a group of high-level officials appointed by their governments to facilitate national action on mass atrocity prevention. R2P Focal Points help in mainstreaming atrocity prevention throughout institutions within their home governments. By meeting globally within the network, R2P Focal Points help ensure that strong inter-governmental partnerships are formed that can not only facilitate the sharing of best practices at the national level, but may also aid in developing relationships for bilateral assistance in building state capacity for prevention. Both the Global Network of R2P Focal Points and the Latin American Network for Genocide and Mass Atrocity Prevention have invited civil society participation at their meetings and encourage member states to consult civil society on building domestic mechanisms for prevention.

In 2013, the growing emphasis on prevention came to the forefront in a variety of ways. The UN Secretary-General’s annual report on R2P focused on the responsibility of the state to its population. The report, and subsequent UN General Assembly interactive dialogue on the subject, highlighted measures that states have already taken in order to prevent mass atrocities within their borders. Prior to the publication of the report, the Joint Office of the Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide and the Responsibility to Protect conducted consultations with member states and civil society members to construct an inventory and assessment of domestic measures for atrocity prevention. More than 120 states participated in consultations and over 65 participated in the annual dialogue, 10 more than in 2012 and 25 more than 2011, showing that more states than ever are engaged in ensuring that mass atrocity prevention remains a priority on their national agenda.

A critical test for upholding R2P through preventive efforts came in March 2013 during Kenya’s national elections. Violence that followed the December 2007 presidential elections in Kenya resulted in more than 1,133 Kenyans being killed and over 600,000 persons driven from their homes. The conflict was largely propelled by incitement to violence, the use of hate speech and the manipulation of the ethnic affiliation to elicit hatred against key political parties. International actors swiftly responded to the inter-communal violence in what is widely cited as the first successful example of “R2P in practice.” Since 2008, the government of Kenya and its international partners have implemented measures to address the underlying causes of the conflict in order to prevent future atrocities. This included structural measures, such as reforming the judiciary and security sector, as well as proximate prevention through pre-election peace messaging, often with the help of civil society, and deploying troops to potential flashpoints. Though the 2013 elections were not without conflict, the preventive measures ensured that the violence did not spread and the government was prepared to respond to early warning of potential atrocities.

R2P, mass atrocity prevention and global governance

Alongside the increased emphasis on prevention, the approach to developing Pillar II mechanisms for R2P is linked to emerging trends within global governance. One such trend is the rising importance of regional organisations. As regional organisations have improved upon their capacity to respond in a timely and decisive manner, states have grown to rely upon their local knowledge of a crisis to act as first responder. Evidence of this trend is particularly strong in West Africa, where the African Union (AU) and Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) have both played a large role in conflict prevention and crisis response in their member states. For example, in response to the 2012 coup in Mali, both organisations actively pressed the UN Security Council to support the creation of a peacekeeping mission, while ECOWAS also imposed economic sanctions and negotiated a transfer of power away from the military junta. They have each devoted resources to developing preventive mechanisms, including the creation of regional and sub-regional early warning networks that share information on emerging crises. Additionally, both have preventively responded to emerging conflicts in order to avert an escalation to mass atrocities, utilising such tools as early mediation and suspending states from membership of their organisations. ECOWAS’ early warning system also includes a role for civil society: the West African Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP) assists in monitoring dynamics between populations within West African countries.

Another critical shift in global governance that R2P benefits from is that, like states, international institutions are starting to take a whole-of-government approach to addressing issues within member states. For example, the UN Special Adviser on the Responsibility to Protect, Dr Jennifer Welsh, set as two of her key priorities mainstreaming mass atrocity prevention throughout the UN system and improving tools for assisting states in building atrocity prevention. In addition, as part of the global discussion on the progress towards and future beyond the Millennium Development Goals, states and institutions alike have started to think about where mass atrocity prevention fits within the international development agenda. Within international development institutions, states have started to ask critical questions about how best to address building capacity for mass atrocity prevention through programmes that connect to a variety of societal concerns. Programmes in Kenya funded by the UN Development Programme, UN Women and individual states to address youth unemployment, media capacity and local peace councils are demonstrative of this trend.

What role can civil society play in preventing mass atrocities?

Civil society organisations (CSOs) have already participated widely in advocacy surrounding the promotion of mass atrocity prevention, helping to pressure governments to respond to atrocities, facilitating dialogue between governments and encouraging more international dialogue on prevention. The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, in its role as Secretariat of the Global Network of R2P Focal Points, has directly participated in fostering such inter-governmental relationships. Other actors, including the 70-plus CSOs that are members of the International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect, promote mass atrocity prevention by directly assisting populations and putting pressure on governments to improve their preventive and response capacity. Civil society has also worked to encourage capacity building within regional organisations such as ECOWAS and the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region. Learning from the experiences of civil society actors in countries that are considered R2P “success” cases, governments and civil society can do more to work together. In Kenya and Ghana, for example, peaceful inter-communal relationships have been supported by governmental District Peace Councils. In both countries the District Peace Councils include representation from religious and ethnic leaders within civil society, who convey messages of peace to their respective groups. However, this is difficult to accomplish if the state does not establish transparent lines of communication with civil society.

Allowing the population to participate more widely in national mechanisms for atrocity prevention becomes ever more critical in post-conflict situations, where community leaders can serve a vital role in post-conflict reconciliation processes. Governments and intergovernmental organisations need to engage better with civil society in order to benefit from their perspectives on the reconciliation process.

Conclusion

Many actions taken by the international community provide positive developments towards ensuring the prevention of mass atrocities and the avoidance of past mistakes. Notwithstanding the stalemate on Syria, the UN Security Council has shown its willingness to take more robust action in order to prevent further atrocities. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the newly-created Intervention Brigade, which the Security Council authorised as a part of the stabilisation mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The brigade is mandated to protect civilians through taking offensive measures against armed groups operating in the eastern DRC. Many of these groups, including the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, the Lord’s Resistance Army and various Mayi-Mayi militias, have been operating within the DRC for more than a decade, routinely perpetrating mass atrocities.

Nevertheless, the conflict in Syria demonstrates that more needs to be done to ensure that the willingness to halt mass atrocities is present even in the most difficult cases. As Gareth Evans, co-chair of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, which originated the concept of R2P, notes, “it is important to emphasise that the disagreement now evident in the UN Security Council is really only about how the R2P norm is to be applied in the hardest, sharp-end cases, those where prevention has manifestly failed, and the harm to civilians being experienced or feared is so great that the issue of military force has to be given at least some prima facie consideration.” While R2P has aided in highlighting how existing tools for atrocity prevention and response can be used to prevent further attacks upon a population, it has not yet ignited the will to respond in more challenging situations in a systematic way.

Actions taken by states and international institutions in keeping with the preventive element of R2P are today ensuring that fewer conflicts will escalate to mass atrocity situations. As states work towards addressing the root causes of violence, establishing good governance and the rule of law and heeding early warning signs, more conflicts can be prevented before they start. In doing so, states should use civil society as a resource, consulting them on political reforms and encouraging them to spread messages of peace, reconciliation and human rights understanding to the population. So long as states continue to implement reforms and share best practices through formal dialogues and informal information sharing, the international community will continue to develop better mechanisms for prevention. Through early effective prevention we can ensure that we will not make the same mistakes in answering the call of “Never Again.”

Related Content