It’s Not Too Late to Save Kyrgyzstan

The following article written by James Traub was originally published in Foreign Policy.

Russia and the United States weren’t able to stop the recent outbreak of violence and ethnic cleansing in Osh. But there’s still time to prevent the worst.

In 2005, the world’s heads of states, gathered at the United Nations headquarters in New York, agreed that they had a responsibility to protect their own peoples from mass atrocities — and that the responsibility would fall to the larger community when a state proved unable or unwilling to prevent such crimes. Since that time, violence reaching the legal threshold of crimes against humanity (the other specified constituent crimes are genocide, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing) has been perpetrated in Sudan, Sri Lanka, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and arguably in Kenya, Burma, and Zimbabwe, among other places. In almost every case, the world has failed to muster an even remotely effective response. So far, it looks like we can add Kyrgyzstan to the list; but it’s not too late to get things right.

In the explosion of ethnic violence that rocked the southern city of Osh starting June 10, as many as half the country’s 800,000 Uzbeks were forced to flee their homes before marauding mobs of ethnic Kyrgyz, apparently abetted by government troops. An untold number, which the New York Times now puts at “thousands,” have been killed. Arson, rape, and other atrocities have been widespread. Late last week, the very fragile government in Bishkek finally seemed to gain control over the army; or perhaps, with the victim population largely terrorized and dispersed, the violence simply burned itself out. But this might be the lull before another storm: Uzbeks may seek revenge, in turn provoking new attacks from Kyrgyz or from the Kyrgyz-dominated security forces. Naomi Kikoler of the Global Center for the Responsibility to Protect calls the violence “a textbook case of R2P,” as the norm has come to be abbreviated. Her organization as well as Human Rights Watch and the International Crisis Group have called for urgent international action.

In the first moments of the crisis, Kyrgyzstan’s interim president, Roza Otunbayeva, issued a desperate call to Moscow to provide troops. Instead, Moscow referred the matter to its own regional body, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which then declined to authorize action. Russia had cited R2P — with transparent cynicism — to justify its 2008 invasion of South Ossetia and Georgia. Why not now, with a willing government and a genuine crisis? It is morally satisfying to say, as human rights advocates often do, that nobody is acting because nobody cares. And that’s often true: The death of several hundred thousand Darfuris weighed far less with most states than assuring “African solutions to African problems” or preserving commercial ties with an oil-rich regime. But Kyrgyzstan, the world’s only country with both a

U.S. and a Russian military base, is scarcely a geopolitical orphan; and because the government, in this case, is not perpetrating the atrocities, potential actors do not have to defend a regime at the cost of neglecting citizens.

Whatever its strategic or moral preferences, Russia faced an extremely daunting calculus, as Peter Zeihan, an analyst for Stratfor, which provides “strategic intelligence,” pointed out in a recent article. Kyrgyzstan is 1,800 miles from the Russian heartland and has a rugged geography and little economic value. There is also the huge complicating factor of Uzbekistan, which borders the inflamed area, aspires to be the regional hegemon, and would almost certainly have objected to the Kyrgyz request. Indeed, any dispatch of Russian troops to the periphery would have instantly reminded both Russians and their neighbors of very painful experiences in Afghanistan and Chechnya. The CSTO is widely viewed in the West as Russia’s Potemkin NATO, but Moscow would have been loath to act unilaterally in the face of opposition from other members (one of which is Uzbekistan). Finally, ethnic Uzbeks were the victims — and “Russians and Uzbeks don’t like each other,” as Stephen Sestanovich, a Russia expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, puts it bluntly.

And why didn’t the United States act? There have been reports that Otunbayeva also asked Washington for help. A senior administration official says that the rumors are untrue, though an unofficial appeal might have been made to U.S. diplomats. Such a request, he insists, “would have been taken very seriously,” but it’s hard to believe that President Barack Obama would have ordered troops transiting the NATO base at Manas for Afghanistan to form a convoy to Osh. Indeed, asking neighbors to send troops to suppress atrocities within days of their outbreak, especially if they might have to take on a local army, is a test the international community is very likely to fail.

But military force is only one, and not necessarily the most effective, response to “R2P situations.” In 2008, swift diplomacy prevented post-electoral violence in Kenya from turning into mass slaughter; tough sanctions at the very outset might have halted the killings in Darfur. The current lull in violence in southern Kyrgyzstan, and the eagerness for help displayed by a very weak but democratic regime, gives international actors a second chance to get things right, and without an urgent military intervention.

But will they? The White House, along with other donors and the United Nations, is now focused on helping to organize humanitarian assistance. The deeply insecure environment around Osh has raised the question of whether troops might be needed to secure a “humanitarian corridor,” but because this was precisely the limited mandate of the U.N. peacekeepers who were sucked into a vortex in Bosnia and Somalia, among other places, officials are exploring this approach with extreme caution. A senior U.N. official says that shops in Osh have begun to reopen, raising the hope that supplies can be distributed without military protection.

The threat of renewed violence won’t subside just because refugees are being fed and housed; returning them to their homes might, in fact, exacerbate the situation. The U.N. official to whom I spoke was surprisingly sanguine about reconciliation, hoping that a June 27 referendum that would give permanent status to the interim government would strengthen the regime’s capacity to act. The Security Council discussed Kyrgyzstan once last week, and neither Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon nor council members have shown much urgency on the subject. But the White House has been engaged in virtually round-the-clock consultations on mechanisms to prevent another outbreak of violence, along with Russia, various allies, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, whose current head is Kazakhstan. Here, too, it might be necessary to ask the Security Council to authorize some kind of “stabilization mission,” perhaps involving police or constabulary forces rather than peacekeepers. The administration official said policymakers are considering “a dozen alternatives” and haven’t yet come up with the right one, much less marshaled whatever forces would be needed to implement it.

This official also said that the one positive thing to come out of an otherwise tragic situation is the close cooperation between Russian and U.S. diplomats and political leaders, and Kyrgyzstan will certainly be on the agenda when Obama and President Dmitri Medvedev meet June 24. That certainly is a bonus, and perhaps even a validation of the “reset” with Russia. But if the two former adversaries work together to make a really, really sincere effort that fails to stop a new round of violence, that will be to no one’s credit.

Russia may be cynical on R2P, but this U.S. administration is not. In his National Security Strategy released last month, Obama vowed to remain “proactively engaged in a strategic effort to prevent mass atrocities and genocide.” Last summer, when the Sri Lankan government killed thousands of civilians in its campaign to wipe out a vicious terrorist group, the administration worked quietly, and as it turned out ineffectively, to stanch the violence. Kyrgyzstan presents an easier test — about as easy as R2P situations are likely to get. This time, no points for trying hard.

Related Content

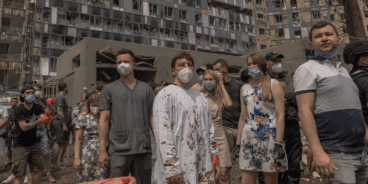

Atrocity Alert No. 402: Ukraine, Myanmar (Burma) and Nigeria