Diplomacy and Double Standards

The following article written by Prof. the Hon. Gareth Evans was originally published in Project Syndicate.

When does acceptable diplomatic caution and realism become indefensible abdication of moral standards? Not everyone on the foreign-policy frontline cares, but those who do often face deeply uncomfortable choices.

Negotiating a life-saving peace may mean giving amnesty to the murderously guilty. Living with tyranny might be less life-threatening than embracing anarchy. Calming a volatile situation may mean not publicly denouncing behavior that cries out for condemnation. Making the right call is more difficult in the real world than in a philosophy classroom.

But sometimes the line really is crossed, all relevant players know it, and the consequences are potentially profound. The United States’ failure so far to cut off its military aid to Egypt in response to the regime’s massacre of hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood supporters, in the streets and in prisons, is as clear a recent case as one can find.

Former President Mohamed Morsi’s government was a catastrophic failure – ruthlessly ideological, economically illiterate, and constitutionally irresponsible. It deeply polarized a society yearning for a new inclusiveness. But, had the army held its nerve – and triggers – there is every reason to believe that Morsi would have been voted out in the next election. If the Muslim Brotherhood denied a ballot, or refused to accept defeat, tougher measures could then have been contemplated. As it is, the army’s coup was indefensible, and its slaughter of mostly unarmed protesters ranks in infamy with the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989, and those of Libya’s former leader, Muammar el-Qaddafi, and Syria’s Hafez and Bashar al-Assad.

It is not as if maintaining its $1.3 billion in annual military aid gives the US any leverage over Egypt’s behavior. It might have once, but the amount now pales in significance next to the $12 billion in economic assistance recently rushed to the generals by Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates. Certainly, the regime would resent withdrawal of this aid, as would most of the Brotherhood’s civilian opponents; but that matters less than the impact on American credibility, in the Middle East and the rest of the world, of not doing so.

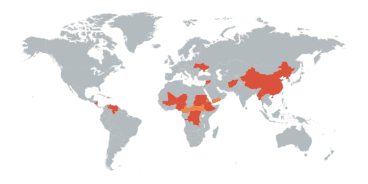

Unless political leaders know that tearing up the rule book on the scale seen in Egypt will expose them to more than rhetorical consequences, the tacit message – that regimes that pick the “right” targets can repress at will – will resonate in Bahrain, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia, not to mention Syria. Farther afield, the US risks reinforcing the perception that it is comfortable with double standards. For a country whose global leadership depends as much on its soft power as on its military might, that is dynamite.

The charge sheet here is already rather full, with multiple instances in recent years of America being almost universally regarded as not practicing what it preaches. For starters, there was the invasion of Iraq in 2003: Embracing the United Nations Security Council when you get your way, but bypassing it when you don’t, does not do much to encourage a cooperative rule-based international order.

Then there was the Palestinian election of 2006: Promoting democracy generates ridicule when it extends only to elections that produce palatable winners, as Gaza’s vote for Hamas did not. Or, again in the Middle East, there has been the blind eye endlessly turned to Israel’s actual possession of nuclear weapons, in contrast to the response to Iran’s possible early moves in that direction. And there was the 2008 agreement to trade nuclear material and technology with India, despite its unwillingness to accept serious new disarmament or non-proliferation commitments.

To be fair to the US, such double standards abound among other major powers as well. Russia’s invocation of the “responsibility to protect” to justify its 2008 invasion of Georgia was met with incredulity at the time, and rendered even more cynical by its resolute failure since 2011 to condemn the Syrian regime for mass-atrocity crimes against its own people.

China’s strategic aspirations in the South China Sea, and its unwillingness to embrace a maritime code of conduct there, sit uncomfortably with its stated concern for sovereign boundaries and the peaceful resolution of territorial disputes. And every one of the nuclear-armed states has been guilty of “do as I say, not as I do” in insisting on non-proliferation while making no serious commitment to disarmament.

To be fair to diplomatic policymakers everywhere, it is often the case that hard choices between competing moral values – for example, justice and peace – simply have to be made. And positions that are claimed to embody double standards are often nothing of the kind. A good example is the allegation that the “responsibility to protect” principle is inherently flawed, because the major powers will always be immune from intervention, not only because five of them can exercise a Security Council veto, but also because of their inherent military strength.

But this ignores the principle that no military intervention will ever be legitimate unless it satisfies, among other criteria, the test of diminishing, not augmenting, human suffering. And going to war against any of the major powers to protect a suffering minority would certainly trigger a much wider conflagration.

The bottom line is that values matter in international relations, and states that place great emphasis on the promotion of values are extremely vulnerable to charges of hypocrisy. No state that aspires to win the support or cooperation of others can afford to be seen to be comfortable with unambiguous double standards. And worst of all is to be perceived as being soft on those who, like Egypt’s current military rulers, commit mass-atrocity crimes against their own citizens.