Cyclone Nargis: Whose Responsibility to Protect?

Thursday, 12 June 2008 | 9:30 to 11:00 am | The Segal Theatre at The CUNY Graduate Centre 365 Fifth Avenue, New York City

The June 12 panel–“Cyclone Nargis: Whose Responsibility to Protect?”–produced sharp disagreement not only about whether the Burmese regime’s dilatory response to the cyclone constituted a potential “R2P situation,” but also more broadly about the role of this new doctrine in the aftermath of natural disasters. While none of the panelists or audience members found much to praise in the junta’s humanitarian response, some sought to understand the “paranoia” that the country’s leaders bore to the outside world. They concluded that outsiders eager to help victims of the cyclone would have to either work around the barriers erected by the fearful and suspicious generals, or look for those in the regime more open to engagement with outsiders. The regime, one participant noted, was far less monolithic than it appeared from the outside.

Others felt that the regime’s state of mind mattered far less than the effect of its behavior on its own beleaguered citizens. One participant catalogued the lethal diseases, including HIV and malaria, which had proliferated in Burma owing to a moribund public health system—at a time when the sale of natural resources was enriching members of the regime. The unnecessary death of perhaps 100,000 citizens made the regime criminal even before the cyclone struck, which meant that Burma had arguably been an R2P situation for years. This participant and others nevertheless did not view the regime’s neglect of its citizens in the aftermath of the cyclone as meriting the application of the responsibility to protect. Another participant, however, said that the very real possibility of mass death from neglect meant that the Security Council should have taken up the issue and noted that the council had even rebuffed a proposed briefing by UN humanitarian coordinator John Holmes.

What was the effect of raising the specter of R2P in the case of Burma? One participant argued that the calls for outside action persuaded the regime that it was facing attack and derailed efforts by neighbors to build the necessary trust required for greater humanitarian access. Humanitarian aid ought not be “politicized,” according to this participant, who argued that the incident actually had damaged R2P by persuading many countries that it would be loosely invoked beyond the boundaries set by the 2005 UN World Summit Outcome Document. Another participant demurred, saying that the cyclone had deteriorated into a “man-made crisis,” and thus at least potentially fell within the ambit of R2P; moreover, the harsh worldwide criticism might have pushed the Burmese junta to cooperate with regional authorities more quickly than it would have otherwise. And one participant noted tartly that R2P was not a “delicate vase” but a “sturdy pot,” which states must be willing at times to take down from the shelf and use.

And if it had been used, could aid have been effectively delivered absent consent from the regime? Here, too, there was vigorous disagreement among panelists and members of the audience. One participant stated that ships stationed just offshore in the Irrawaddy Delta could easily have off-loaded supplies and medical personnel on flat boats to access some of the most remote communities. With the regime permitting aid to reach no more than half the 2.4 million afflicted citizens, ought such a non-consensual option at least not have been considered? Not according to another participant, who argued that the regime would have seen such an effort as the first sally of an invasion, and instantly dispatched troops to the area. Neither in Burma nor elsewhere should aid be delivered over the direct objections of the state in question.

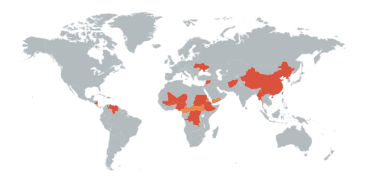

How, then, should one understand this emerging norm, especially in the context of the United Nations, an organization of states that has traditionally treated sovereignty as sacrosanct? One participant described R2P as the latest stage of an evolving recognition that states can not simply do as they wish to their citizens. Others were far less enthusiastic, including one who criticized the discussion as politically naïve and an illustration of why many developing countries perceived R2P as a license for the West to stage interventions. As such, it would remain an “orphan” of humanitarian law. R2P should be fitted to states’ legitimate concerns about sovereignty.

The session ended with an intensely practical question. If the Security Council is not likely to authorize coercive action save in the most extreme cases, what will the international community do when faced in future with these very real catastrophes?

Speakers

-

-

- H.E. Mr. Vanu Gopala Menon Permanent Representative of the Republic of Singapore to the United Nations

- H.E. Mr. Jean-Maurice Ripert Permanent Representative of France to The United Nations

- Aryeh Neier, President, Open Society Institute

-

Respondent

-

-

- Charles Petrie, UN Special Advisor, former UN Resident And Humanitarian Coordinator in Myanmar

-

Chair

-

-

- James Traub, Director of Policy, Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect

-

Related Content

R2P Monitor, Issue 70, 1 September 2024