Stopping mass atrocities and promoting human rights: My work as the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

On 29 October Ms. Navi Pillay, former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, delivered the Fourth Annual Gareth Evans Lecture. Her speech is entitled, “Stopping mass atrocities and promoting human rights: My work as the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.”

I am very pleased to deliver the Gareth Evans lecture this year and thank the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect for their kind invitation. I join in paying tribute to Professor Gareth Evans for his pioneering work on the R2P concept and his contributions to conflict prevention and resolution, as well as on arms control and disarmament.

As you know, I stepped down six weeks ago after serving as UN High Commissioner for Human Rights for six years. I look back with great pride at the achievements of the OHCHR and its highly committed staff in advancing the protection and promotion of human rights and the right to development. At the same time, I am deeply disturbed by the current raging conflicts in several countries. The UN Secretary-General spoke of his despair as he takes the lead in confronting the extraordinary demands made upon the UN to provide peacekeeping support and humanitarian aid. In these worst of times, “are human rights still relevant? And has R2P helped or hindered the advancement of human rights protection?”

These are questions that are often put to me by journalists. These questions go to the heart of a lifetime’s work on human rights by Gareth Evans and many of us. The importance of a lecture series such as this is the opportunity it offers for review and assessment, including challenges to R2P.

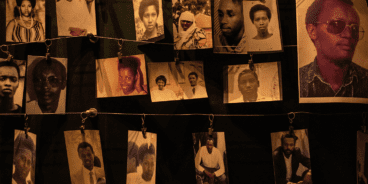

The gas chambers of Auschwitz, the killing fields of Cambodia and Rwanda, and the mass graves of Srebrenica will always remind us that the world must never stand by and allow mass atrocities to take place. At the World Summit of 2005, Heads of State and Government solemnly recognized that that every state and the international community as a whole have the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.

The Summit declaration is a resounding endorsement that international law is norm based: It embodies human rights, democracy, good governance and the rule of law and moves away from the state-centered system of traditional international law based on the preeminence of sovereignty. The goal of international law, while respecting freedom of sovereign states, is also to protect and promote peace, security, development and human rights.

As we approach the tenth anniversary of the World Summit Outcome Document next year, it is important that we renew efforts for its sustained implementation.

The Outcome Document statement on R2P has three components.

-

- In accordance with the notion of state sovereignty as responsibility for the most basic tenets of international human rights law, it is first and foremost the responsibility of each state to protect its own population against atrocities.

- At the same time, the leaders gathered at the World Summit of 2005 recognized when necessary, the international community should assist states in implementing the responsibility to protect their own population. This is critical where states are confronting powerful armed rebel groups committing atrocities against the population.

- Finally, where a state manifestly fails to protect its own population, the international community has a responsibility to protect, which it must exercise using the means prescribed and circumscribed by the Charter of the United Nations.

R2P remains alive and highly relevant for today’s challenges.

I shall make some remarks on the notion of sovereignty, international intervention and finally on assistance to states.

State sovereignty is often invoked to deflect UN action to prevent serious human rights violations. But as I have often said to representatives of governments, “You made the law; now you must observe it.” I underscore the underlying legal obligations incumbent upon states, flowing from their own national laws and international law to which they all subscribe, to act to protect when gross violations of human rights or other international crimes are occurring.

Sovereign states established the UN, and built the international human rights framework, precisely because they knew that human rights violations cause conflict and undermine sovereignty. Early UN action to address human rights protects states by warding off the threat of devastating violence and forced displacement.

A broader conception of national interest would be more appropriate to a century in which a growing number of challenges face humanity as a whole. In these terms, I suggested to the UN Security Council in my address to it on 21 August this year, that the use of the veto to stop actions intended to prevent or defuse conflict is a short term and ultimately counter-productive tactic. The collective interest – defined clearly by the UN Charter – is in the national interest of every state.

Human rights are always central to conflict prevention. Patterns of violations, including sexual violence, provide early warning of escalation. The human rights agenda is also a detailed road map for ways to resolve disputes. The years of practical experience of OHCHR, including through human rights components of peacekeeping missions, demonstrate a number of good practices that address both proximate triggers of conflict and root causes. To emphasize three, let me highlight strengthening civil society actors, increasing participation by women in decision-making and dialogue and addressing institutional and individual accountability for past crimes and serious violations of human rights.

And yet the conflict in Syria is metastasizing outwards in an uncontrollable process whose eventual limits we cannot predict. It has taken almost 200,000 lives and forcibly displaced millions of Syrians, now cramped in UN shelters in neighboring states with resulting huge cost to them and the UN. The conflict has spawned tentacles across the borders into Iraq.

The atrocities being perpetrated by the ISIL group in Iraq have reached unimaginable levels. Thousands of men, women and children have been executed and forcibly recruited, while girls have been sold into sexual slavery and women raped.

Imposing its own extreme form of Islam, ISIL offers no other option to its captives but to convert or be slain. When I was High Commissioner I issued a statement condemning the large scale attacks and intolerance towards the Christian population. However, no religious or ethnic group is safe as ISIL continues expanding its vast area of control. Employing sophisticated modern technology of the digital era, ISIL has managed to spread its Jihadist propaganda and recruit young fighters across the world in a most insidious manner.

The Government of Iraq, unable to contain this massive conflict, especially when confronted by Syrian and foreign insurgents, has asked for international assistance to help it protect its people.

Other complex and potentially highly eruptive conflicts are underway in Afghanistan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Libya, Mali, the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Ukraine.

These crises hammer home the full cost of the failure of the international community to exert their Responsibility to Protect and prevent conflict. They combine massive bloodshed and devastation of infrastructure with acutely destabilizing transnational phenomena, including terrorism, the proliferation of weaponry, organized crime and exploitation of natural resources.

None of these crises erupted without warning. They built up over years – and sometimes decades – of human rights grievances: deficient or corrupt governance and lack of independent judicial institutions, discrimination and exclusion, inequities in development, exploitation and denial of economic and social rights, and repression of civil society and public freedoms.

Early detection systems – such as the 51 Special Procedures experts of the Human Rights Council, and systematic scrutiny by treaty bodies, repeatedly alerted us to these shortfalls. So, although the specifics of each conflict could not necessarily be predicted, many of the human rights violations that were at their core were known. They could and should have been addressed.

This was, in the first place, the duty of the relevant states. But when Governments are unable or unwilling to protect their people, international law is clear: it is the responsibility of the international community, through its various UN system bodies, but specifically, the Security Council, to intervene and to deploy the range of good offices, support, inducements and coercion at its disposal to defuse the triggers of conflict.

I am extremely grateful for the many opportunities opened to me to place these concerns before the Security Council. The Council’s interest in human rights has increased markedly during my tenure with a growing acknowledgment that it cannot safeguard international peace, security and development without being alerted to the situation of human rights.

But despite repeated briefings regarding escalating violations in multiple crises, by OHCHR and other human rights mechanisms, and the Secretary-General’s appeal for greater collective action, there has not always been a firm and principled decision by members to put an end to conflicts. Short term geopolitical considerations and national interest narrowly defined, have repeatedly taken preference over intolerable human suffering and grave breaches of – and long term threats to – international peace and security.

The third component of the R2P concept is the call for the international community to intervene when a state fails or is unwilling or unable to protect its people. The protection of civilians is another related, but distinct, principle. While R2P can apply outside the context of conflict, protection of civilians is applicable specifically to conflict situations, mainly in the context of peacekeeping operations. Both principles are applicable for ensuring the protection of communities from atrocities and both place a responsibility on the international community to intervene and ensure such protection where a state fails or is unable to do so.

On 23 July 2009, during the debate on the Secretary-General’s report on R2P in the General Assembly, concerns and misgivings were expressed by some states as to the derogation of the principle of state sovereignty. The Non-Aligned Movement argued that R2P could be misused “to legitimize unilateral coercive measures, or intervention in the internal affairs of states.”

Ultimately, the General Assembly merely took note of the Secretary-General’s 2009 report, and did not endorse R2P as a principle of international law or recognize its role. The interventionist provision of R2P continues to be problematic for states, particularly when it is used as justification for military intervention in internal conflicts.

The Libyan experience is often cited by members to resist the exercise of collective application of R2P in the Syrian conflict.

UN Security Council Resolution 1973 (2011), adopted for the purpose of protecting civilians and exercising R2P for all Libyans, authorized the use of force under the term “use of all necessary measures.” While consistent with other Security Council resolutions on the use of force, Resolution 1973 does not place the use of force under the Security Council’s operational control, but rather authorizes a “coalition of the willing and able.”

Questions have been raised on whether the delegation to the willing and able was a permissible delegation, and whether by so doing the Council relinquished its supervisory obligation. The resolution does require reporting through the Secretary-General, presumably to act as some form of control.

As the Libyan operations ensued, there arose a groundswell of reaction against the heavy and lengthy aerial bombing carried out by NATO, perceived by some, including abstaining member states, that NATO had gone beyond the protection of civilians and instead was intent on ousting Gaddafi. Statements attributed to states’ representatives did not help to allay this concern.

There were allusions to facilitating the movement of rebel fighters by removing Gaddafi and that the bombing would not stop until he was “taken out.” As High Commissioner, I condemned the unlawful killing of Gaddafi and called for a full and independent investigation.

Since the Security Council resolution authorized the use of force under the mantle of protection of civilians and R2P, in an operation that ended in regime change, questions were raised as to whether regime change is a means of giving effect to the legitimate principles of R2P and protection of civilians.

Lest the R2P concept loses support, it is important to address the concerns raised. It is clear that the concept itself cannot be faulted. As far as I can see, no objection has been raised to the concept itself but to its application and implementation.

R2P, like human rights, must never become politicized, employed selectively or be the weapon for double standards and regime change.

I turn now to consideration of the second component of R2P, namely, assistance to states to implement R2P.

In my address to the UN Security Council on prevention of conflict, I suggested that the Council could take a number of innovative approaches to prevent threats to international peace and security. Within “Rights Up Front,” the Secretary-General can be even more proactive in alerting to potential crises, including situations that are not formally on the agenda of the Security Council. To further strengthen early warning, the Council could also ask for more regular and comprehensive human rights reporting by protection actors.

The Secretary-General’s Rights Up Front action plan is an important initiative for collective and immediate delivery by all UN agencies for the protection of human rights in crises. It was a welcome development stemming from the UN’s failure to protect in the Rwanda and Sri Lanka situations. I must express appreciation for the firm and steady measures put in place by the SecretaryGeneral, despite the numerous crises, for the UN to render assistance to states in the implementation of R2P.

I recall that the Human Rights Council has played and will continue to play an important role in developing and implementing the Responsibility to Protect. When crimes and violations covered by R2P occur, the Human Rights Council provides a representative international forum to urgently convene states, notably through special sessions and urgent debates. On occasions, the Human Rights Council has sent a united and strong signal that such atrocities will not be tolerated, and that individual perpetrators must be brought to account.

Commissions of Inquiry (COIs) and other fact-finding mechanisms are also invaluable. They provide a means to gather objective and up-to-date information and their recommendations point to appropriate national or international action to curb the crimes and violations covered by R2P.

Recent COIs include: the Security Council’s COI for Central African Republic, the Human Rights Council’s COIs for Gaza, Syria, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Eritrea and Libya, and the African Union’s COI for South Sudan, as well as investigation reports to the Human Rights Council on Sri Lanka and Ukraine.

Let me stress that having to react to past or ongoing atrocities implies that we have already failed to protect. The most effective way to implement R2P lies in the prevention of relevant violations and crimes before they occur. It is at this stage that the international community can and should be most effective.

The crimes and violations covered by R2P never happen without warning. They occur because warning indicators such as persecution of minorities, hate speech, patterns of discrimination, sexual violence, child soldier recruitment or rapid deterioration of the economic situation are not perceived or understood, or they are deliberately ignored. As a judge on the UN’s Rwanda Tribunal I was moved by the testimony of witnesses in the Rwanda genocide trials that hate speech was spread over the years like small drops of petrol that eventually set the whole country on fire.

I would like to encourage states to closely study the information and insights generated by Special Procedures and Treaty bodies, which can provide early warning. In a similar vein, the UN should ensure that the reports and recommendations of its Special Procedures bear more systematically and effectively on its decisions and outputs, including through the Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review.

I welcome the occasions on which the Human Rights Council has supported initiatives of OHCHR to deploy monitors or set up field presences in situations of risk, often with the invitation to report back to the Council on their findings, such as in Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine. These monitoring, reporting and early warning activities should be expanded as and when needed.

As for international assistance to states who need support in implementing R2P, the Human Rights Council can signal human rights-based priorities to donors and bodies that coordinate humanitarian and development assistance, as well as peacebuilding efforts. This can help ensure, for instance, that there is effective support for national rule of law and human rights institutions that curb grievances and tensions lying at the root of mass atrocity crimes. Greater support is necessary for technical assistance to initiatives of OHCHR aimed at developing national capacity to prevent gross human rights violations.

In conclusion, I welcome the optimistic remarks of my successor, High Commissioner Zeid Raad Al Hussein:

“Human rights are now being widely upheld in more countries than ever before. It seems to me that the broad trajectory of humanity is a positive one, and that in an increasing number of communities and countries, all human beings are seen as fully equal in dignity, and their rights are largely observed. Within families and within nations, despite all the violations and conflicts I listed earlier, violence and discrimination have, broadly speaking, decreased in the past few decades, and continue to do so.

Credit for that should go to all those countless brave and committed men and women – civil society activists, journalists, lawyers, state employees and politicians – who over the decades have eventually succeeded in firmly rooting international human rights norms in their societies. It is our job, in the UN Human Rights Office, to help them as best we can.”

Thank you.